Margaret Mead once said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” This quote perfectly describes the book Mountains Beyond Mountains, a thrilling biography of the life of Dr. Paul Farmer, by Tracy Kidder. Dr. Farmer epitomizes the founding tenets of medicine, devoting himself to curing patients of their ailments at any cost.

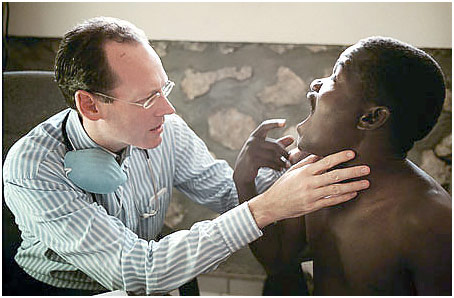

Dr. Farmer

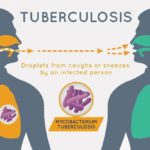

When Dr. Farmer first went to Haiti, he witnessed the poverty and lack of adequate healthcare there firsthand. The experience stuck with him, and he found himself unable to leave Haiti because he believed he needed to help the people there. He set up a hospital Zanmi Lasante in Cange, an arid region in Haiti filled with some of the most destitute people in the world where most houses had dirt floors and thatched roofs. He needed to treat poverty along with a symptom of poverty, sickness. Soon enough, he built schools to increase literacy among the people, and he improved communal sanitation. However, he mainly focused on treating and curing tuberculosis and HIV. Many criticized him for not being sustainable because he provided free treatment to all even though the drugs needed to treat these diseases were very expensive and could never be paid for by the Haitians. He did not listen to their criticism because he only saw it one way: he needed to provide high-quality healthcare regardless of the cost to some of the people that needed it the most. To pay for the enormous bills that this hospital was generating, he began his charity Partners in Health to funnel money from donors to his projects in Cange. Dr. Farmer once remarked that he could not get any sleep because there was always a patient not getting treatment. Whenever he would focus on a goal, he would see it to the end. Haitians saw him as a god, thinking that he had the gift of healing. Indeed, he profoundly affected the lives of many destitute Haitians, saving them from an otherwise miserable fate.

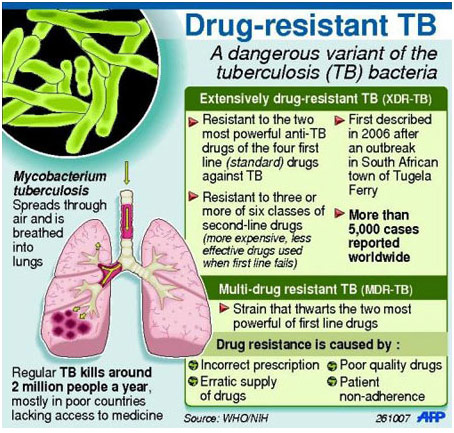

One of the biggest battles that Dr. Farmer fought was the battle against the World Health Organization to recognize multidrug-resistant tuberculosis as a disease that was feasible to treat. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis is a strain of tuberculosis that is caused mostly because of inadequate treatment (perhaps due to interruptions) or improper therapy. The bacteria would undergo many mutations and become resistant to many cheap first-line drugs, making the disease very difficult to cure at that point. Treating MDR required expensive second-line drugs, some of which had very severe side effects, to be administered, and sometimes that was not enough to cure the patient either. The WHO issued guidelines on how to treat tuberculosis in its DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course Chemotherapy) program. The guidelines called for treating patients with one first-line drug at the start. If there were no results, then the doctor was supposed to treat the patient with that same drug plus one other first-line drug. While this worked in Africa where noncompliance or treatment being interrupted was the primary reason for increased resistance to tuberculosis, this was not the case in many countries, for example, Peru where patients took their medications under direct observance of hospital staff. Dr. Farmer deduced that the real reason for their MDR was improper therapy under the DOTS program. He thought that “they had gone to the clinics with one- or, more likely, two-drug resistance, and through treatment and repeated retreatment under the standardized DOTS formulas, they had emerged with four- and five-drug resistance” (Kidder 139). By listening to their doctors, they had actually become sicker. Dr. Farmer pushed for MDR treatment to become acceptable and more of a norm, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. They would say that MDR was too expensive to treat or DOTS would solve MDR in the long run. While he knew that DOTS would not solve MDR, only making it more of a problem, he knew that MDR was very expensive to treat, and it took him one million dollars to treat ten patients with MDR in Peru. He soon realized that the main cost associated with MDR was the cost of second-line drugs because there was virtually no demand for them under the then-current WHO guidelines. He had one of his allies in the WHO set up the “Green Light Committee,” which became the distributor of second-line MDR drugs, and this prompted the WHO to put second-line MDR drugs on the essential drugs list. Thus, he was able to reduce the price of second-line drugs by over 95% in some cases, making it feasible for governments to treat MDR and saving hundreds of thousands of lives that would not be thought of as cost-effective enough to save before.

In one particular instance, there was a Haitian boy in Cange named John who had nasopharyngeal carcinoma, a rare type of cancer that could not be treated in Haiti. Without thinking twice, Dr. Farmer decided to try to bring him to Mass General Hospital in Boston, which had the facility and the doctors to cure John’s syndrome. The doctors at Mass General decided to take John’s case for free, which normally would have cost over $100,000. However, it took a few months to make the diagnosis, get the passport/visa, and prepare transport for John to Mass General. In fact, when they were finally about to take him there, he had been given a tracheotomy, which is an “opening surgically created through the neck into the trachea (windpipe) to allow direct access to the breathing tube” according to John Hopkins. Moreover, he was having secretions that were clogging his airways that needed to be sucked out with a machine (Kidder 266). He was unable to go on a commercial flight, so he went on a Medevac to Boston, costing Partners in Health over $18,000. Nevertheless, the boy died because he had arrived too late and cancer had already progressed throughout his body. Many thought that this $18,000 was wasted on John and could be spent elsewhere on patients who had better chances to survive; however, Farmer vehemently disagreed. He brought him here because “A, he’s a human being, and B, because [Dr. Farmer] didn’t know he couldn’t be treated, and C, why shouldn’t he have a comfortable way to die” (277). Dr. Farmer emphasized the idea of fighting the long defeat. All doctors want and strive to win, but if it means turning their back against a patient who might die or “lose,” then it’s not worth trying to win every time.

I was always interested in medicine ever since taking basic biology in elementary school; however, Dr. Farmer’s story has ignited a passion in me for healthcare. Dr. Farmer is a role model of how to change the world, one saved patient at a time. He represents the epitome of dedication and persistence in medicine, inspiring countless of others like me behind him. He did not do all this for money nor fame; he did it to help the people living in poverty throughout the world who were being ignored by the world. This riveting biography by Tracy Kidder put me in the eyes of Dr. Farmer, leaving me with a new appreciation for medicine and the doctors who shape it.

REFERENCES

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/tracheostomy/about/what.html

http://www.achievement.org/achiever/paul-farmer/