Dr. Nadia Hameed is an endocrinologist, practicing in San Jose. She attended medical school at Rawalpindi Medical College in Punjab, Pakistan, and after completing medical school, Dr. Hameed moved to the USA and began to get certified to practice in the US. After applying to numerous residency programs, she began her 3-year residency at Stony Brook University Hospital & Medical Center in New York for internal medicine. At Stony Brooks, she treated all kinds of patients like those with rheumatology, cardiology, gastroenterology, and oncology problems. She liked endocrinology the best because there was an investigative quality to it. If there was something wrong hormonally with the patient, she had to run tests, rules things out, and finally discover what it was. It seemed like a mystery, and each patient had a different one to solve, always keeping her mentally engaged; she really liked the intellectual part of it. She decided to pursue a fellowship at Oregon Health & Science University in endocrinology for two years where she learned more and more about the specialty. Thankfully, she was kind enough to let me shadow her and see the good kind of work she does. In this post, I will be talking about conditions that patients presented with and treatment for them.

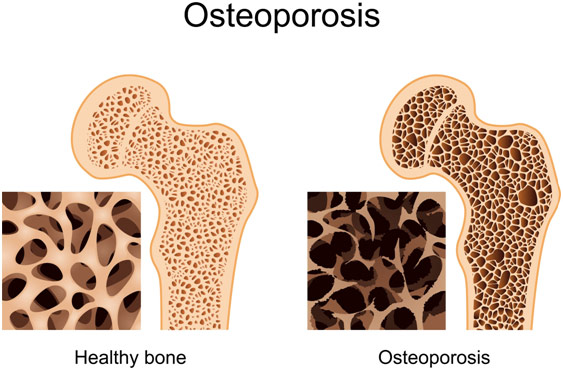

Osteoporosis is a major condition that Dr. Hameed frequently sees. In osteoporosis, bone resorption (breakdown) surpasses bone deposition, leading to weak and brittle bones. The condition is so common that it is advised that all women above 65 and men above 70 should be screened for it. It is also common for osteoporosis to develop after menopause because of the lack of estrogen promotes bone loss. A common risk factor for osteoporosis is also having a history of non-trauma related fracture such as falling from a standing height and breaking a bone. Screening usually occurs in the form of a bone density scan. A T-score greater than or equal to -1.0 is normal, between -1.0 to -2.5 represents having osteopenia (low bone density), and less than or equal to -2.5 signifies a diagnosis for osteoporosis. Moreover, endocrinologists may also test for calcium and vitamin D levels in blood tests, prescribing a supplement if needed. This is because calcium can help build bones, and vitamin D helps the intestines absorb calcium better. For lifestyle changes, doing more weight-bearing exercises like running, walking, Zumba, etc. could be helpful to maintain bone health. In terms of medication, there are some that build bones while others inhibit bone resorption. Forteo (teriparatide) is part of the drug class called anabolic agents that work to build bones. It works by injecting the synthetic parathyroid hormone into the body every day, which raises the number of osteoblast cells, which rebuild bone. However, this is only used in high-risk patients, and it can only be used only for a limited period of time because of the risk of osteosarcoma (bone cancer). Prolia (denosumab) is a part of the drug class called anti-RANKL agents that work to inhibit bone breakdown. It works by injecting human monoclonal antibodies every six months, which bind to the RANKL protein to prevent stimulating the osteoclasts, which break down bone. Alendronate (Fosamax) is part of the drug class called bisphosphonates that similarly work to inhibit bone resorption. It works by binding to the bone and decreasing the stimulus for the osteoclasts, allowing for the osteoblasts to build bone density more.

Healthy Bone Vs. Bone with Osteoporosis

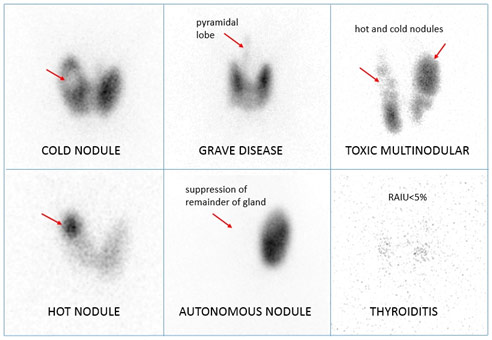

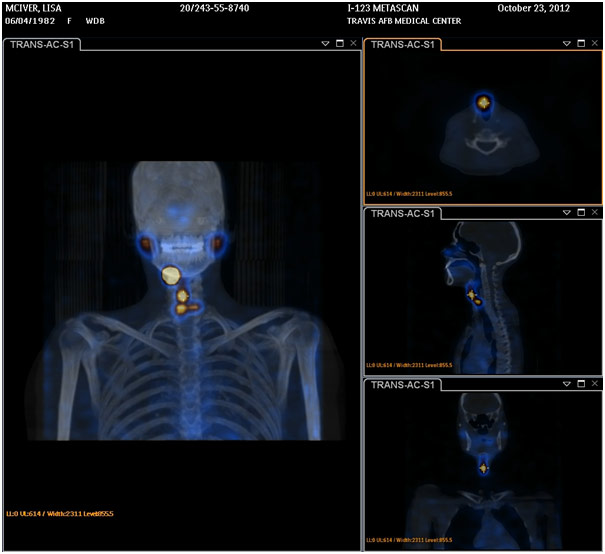

Another major condition that Dr. Hameed sees is Primary Hyperthyroidism. In hyperthyroidism, the thyroid gland produces too much thyroxine hormone despite low levels of TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone). Since thyroxine regulates metabolism, too much can cause symptoms of palpitations, tremors, shakiness, sweating, oversensitivity to heat, and increased bowel movements. Before treatment, it is important to determine the etiology of the hyperthyroidism of which there are three: Grave’s Disease, Toxic Nodule(s), and Thyroiditis. First, endocrinologists do a thyroid-stimulating antibody test to see if it is the autoimmune kind (Grave’s Disease). If it comes back as high, then the endocrinologist knows the etiology, but if it is normal, it does not mean anything because a patient with Grave’s Disease can have normal thyroid-stimulating antibody levels. Thus, the endocrinologist will order a radioactive iodine uptake test. If the etiology is Grave’s Disease, there will be diffused and increased uptake of iodine in the gland. If the etiology is Toxic Nodule (lump(s) in the thyroid that over secrete thyroxine), there will be focal/multifocal areas where the uptake of iodine is high. If the etiology is thyroiditis (temporary inflammation of the gland), then there will actually be low uptake of iodine, and treatment is not necessary. The primary medication for hyperthyroidism is tapazole (methimazole), which is part of the drug class called antithyroid agents. It works by stopping the thyroid gland from overproducing thyroxine by inhibiting iodine from combining with thyroglobulin, lowering peroxidase (role is to makes thyroxine). Endocrinologists do aggressive treatment for 12-18 months, and then they try to taper down, seeing if the thyroid can manage on its own. If it cannot, then radioactive iodine therapy may be considered. It is a cure for hyperthyroidism, which works by injecting a radioactive iodine isotope, which ablates (destroys) the thyroid gland. Patients who receive it cannot be around pregnant women or children for 4-7 days nor can they be within 4 feet of other people since radiation comes out of their body in all directions, which is dangerous for other people. A major side effect of this treatment is that the patient will start having hypothyroidism (low thyroxine) since the thyroid gland is gone. However, this is preferred since the drug to treat hypothyroidism (i.e. levothyroxine) is considerably safer than methimazole.

Radioactive Iodine Scan Results Interpretation

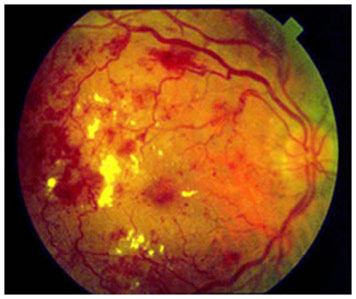

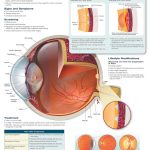

Dr. Hameed mostly sees patients with Type II Diabetes. In Type II Diabetes, the body has a resistance to insulin or the beta cells in the pancreas cannot produce enough insulin, which means blood glucose levels are excessively high. It can be diagnosed if the hemoglobin A1C test is above 6.5%. This test specifically measures glycated hemoglobin, which is glucose attached to red blood cells, which have a lifespan of 120 days. This gives an average of blood glucose levels over a 4 month period; 7% (person with diabetes is recommended to have A1C lower than this) corresponds to an average of about 150 mg/dl. Common risk factors of diabetes are obesity or a family history of it. For lifestyle changes, limiting carbohydrates and other starchy vegetables (potatoes and corn) and eating more lean proteins like fish, chicken, and turkey can be helpful. In addition, eating whole wheat products and fat-free dairy products are other helpful lifestyle changes in regards to food. Lastly, doing 150 minutes of moderate exercise a week can be extremely helpful. The primary medication for Type II Diabetes is Glucophage (metformin), which is part of the drug class called biguanides. It works by increasing the body’s responsiveness to insulin and by lowering the amount of glucose freed by the liver. Another common medication is Victoza (liraglutide), which is part of the drug class called GLP-1 analog. Other medicines in this same drug class include triplicity (dulaglutide), Byron (exenatide), tandem (albiglutide), and lyxumia (lixisenatide). They work by increasing insulin secretion and delaying the movement of food from the stomach to the small intestine so that the patients have early satiety and lose weight. Yet another common medicine is invokana (canagliflozin), which is part of the drug class called SGLT2 inhibitors. Other medicines in this same drug class include radiance (empagliflozin) and Farmiga (dapagliflozin). They work by increasing urinary glucose excretion by inhibiting sodium-glucose co-transporter 2, which is supposed to reabsorb glucose into the blood. The last medications I will be talking about are Humalog (insulin lispro), which is a short-acting (mealtime) insulin, and Lantus (insulin glargine), which is a long-acting insulin. Other short-acting insulins include Apidra (insulin glulisine) and Novolog (insulin aspart). Other long-acting insulins include too (insulin glargine) and tribal (insulin degludec). These both work by providing synthetic insulin to the body to lower blood glucose levels. When an endocrinologist is monitoring diabetes, they will repeatedly order tests for A1C levels, cholesterol levels, kidney/liver function, and a full blood panel among others. The endocrinologist will usually want to fast blood sugar (in the morning before eating anything) between 80-130, but this may vary based on other conditions. Moreover, the endocrinologist will want postprandial sugar (2 hours after a meal) to be below 180, but, yet again, this may vary based on other conditions. Patients usually use a blood glucose meter in order to measure their glucose levels at various times, preferably noting it in a logbook along with what they ate in order to give the endocrinologist a clue if they need to adjust the medications. Complications of diabetes include diabetic nephropathy (kidney filtration problem that can escalate to renal failure), diabetic retinopathy (blood vessels in the retina become damaged and can cause blindness), and diabetic neuropathy (numbness or pins/needles sensation due to intense nerve damage) among others.

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

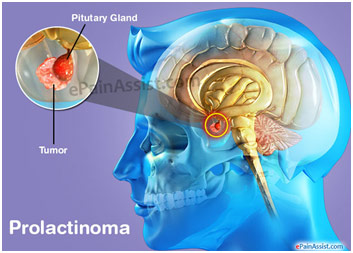

Another condition Dr. Hameed sees is hypogonadism. In hypogonadism, the testicles do not produce enough testosterone either because of the fault of the testes themselves or the pituitary gland. Symptoms generally include fatigue, loss of strength, and infertility because of erectile dysfunction. The doctor can check if it has anything to do with the pituitary by looking at other hormones that are regulated by the pituitary gland like thyroxine or cortisol to name a few. A pituitary adenoma (tumor) such as prolactinoma can cause hypogonadism. This is because the tumor releases too much of the prolactin hormone, which inhibits the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which can cause low testosterone levels. Prolactinoma can be treated with bromocriptine (Parlodel) or Dostinex (cabergoline), which both are part of the drug class called dopamine agonists that work to shrink the tumor and bring the prolactin levels down. If it is not a problem of the pituitary gland, then it must be the testicles’ fault. Sometimes, this may be caused by the use of anabolic steroids, which resemble testosterone, so the body makes less testosterone, thinking it has enough. Testosterone therapy can be used to treat it, available in a gel, patch, nasal spray, and intramuscular injection form.

Location of Pituitary Tumor

One of the most common cancers that Dr. Hameed treats is thyroid carcinoma or thyroid cancer. Dr. Hameed takes a thyroid ultrasound of every patient presenting with trouble swallowing, breathing when lying down, and/or swelling in the neck. First, the endocrinologist checks if the trachea is in the middle of the neck because a big goiter can push it to the side. Next, the endocrinologist will look if there are any abnormally large lymph nodes, and they will measure any nodules in three dimensions. The endocrinologist will take a biopsy of any nodule or complex nodule (fluid and solid parts) above 1 cm. If the nodule has a suspicious appearance like irregular margins, high vascularity, taller than wide, or microcalcification, then the endocrinologist may biopsy it even if it is smaller than 1 cm. A biopsy is a fine needle aspiration where the endocrinologist applies local anesthetic spray and then inserts a 25 gauge needle multiple times into the nodule at different locations. If on the biopsy, there are atypical cells, then the endocrinologist may do an Afirma Thyroid FNA Analysis that looks for genetic markers that may increase risk. This test may come back as positive for aggressive anaplastic or medullary thyroid cancer, or it may come out as suspicious, which gives a 40% chance of papillary or follicular cancer. If the tumor is malignant, then a thyroidectomy will take place to remove one lobe or the entire thyroid. There are benefits and risks to each approach. Taking out one lobe means that the patient may not need thyroid replacement therapy because that lobe can produce thyroxine. However, the second lobe may need to be taken out later anyway if the lymph nodes the surgeon takes out to come back as positive for cancer, indicating local metastasis. Taking out the entire thyroid means that the patient will need thyroid replacement therapy through levothyroxine. However, the benefit of taking out the entire thyroid is that the patient will not need a second possible surgery. Moreover, the endocrinologist can make sure the cancer is gone by testing for thyroglobulin (a protein made by the thyroid gland), which should be undetectable if the tumor is gone. This test does not work if only 1 lobe is still there because the thyroglobulin test will always be positive then. Lastly, radioactive iodine therapy to target any metastatic cancer by ablating any remaining thyroid tissue can only be done after total thyroidectomy.

Thyroid Cancer Recurrence After Total Thyroidectomy and Radioiodine Ablation Detected on I-131 Scan SPECT/CT

Dr. Hameed told me of a story where she treated a patient with pheochromocytoma (PCC), which is when there is a tumor in the adrenal gland, leading to the over secretion of epinephrine. For over 10 years, his disease remained untreated because it is a rare condition that most doctors did not know about. He had palpitations and fainting spells, so he went to a psychologist who thought he was depressed or had anxiety problems and put him on anti-depressants. People thought this illness was simply in his head and that he was going crazy. After a smart physician thought that it may be related to hormone imbalances in the endocrine system, he was referred to Dr. Hameed. She properly diagnosed him with PCC, and surgery was done to remove his tumor. Through the power of medicine, Dr. Hameed helped this man, who was considered crazy by his friends and family for ten years before, return to his regular lifestyle, healthy and disease-free. While shadowing Dr. Hameed, I saw evidence of her thoroughness, resourcefulness, and genuine care for her patient’s well being. How she handled this case along with all the other cases that I observed with her was nothing short of inspirational. She also reinforced the idea to me that medicine has the power to change the world by helping people become healthy again, and doctors are the means through which it all happens.

References

Brown, Susan. “Forteo — Is This Bone Drug Too Good to Be True?” Better Bones, 11 May 2015, betterbones.com/osteoporosis/forteo-bone-drug/. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

“Hyperprolactinoma.” University of Washington, courses.washington.edu/conj/bess/hyperprolactinemia/hyperprolactinemia.htm. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Ogbru, Omudhome. “Methimazole, Tapazole.” Edited by Jay Marks and William Shiel. Medicine Net, 11 May 2017, medicinenet.com/methimazole/article.htm. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Osteoporosis. Jeffrey Sterling MD, jeffreysterlingmd.com/tag/osteoporosis/. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Prolactinoma. EPain Assist, epainassist.com/endocrine/prolactinoma. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Stone Oak Ophthalmology Center, stoneoakeyes.com/diabetic-retinopathy/. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Schaeffer, Juliann. “Injectable Prolia — Osteoporosis Update.” Today’s Geriatric Medicine, 2017, todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/archive/110310p6.shtml. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Singh, Kamal. Thyroid. Nuc Rad Share, www.nucradshare.com/Thyroid.html. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Would you please clarify some things? Your attitude should be accepted and normal for all…it’s just that..There are a few reasons that negate this. I hope so- thanks for your time.

Hello there! Would you mind if I share your blog with my zynga group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really appreciate your content. Please let me know. Cheers

Wow! You certainly covered all important points in this post. I want to read more by you. Do you maintain any other blogs?