Complications: A Surgeon’s Note on an Imperfect Science is a novel about Dr. Atul Gawande’s period as a surgical resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, specifically training to be a general surgeon. This novel includes lot of Dr. Gawande’s brooding on many different aspects of medicine as it related to him and his residency experiences. He explores, with great depth and insight, many ethical and practical problems presented in medicine and how he has learned to deal with them. The book is a must-read for any person who aspires to be a doctor one day.

Dr. Atul Gawande

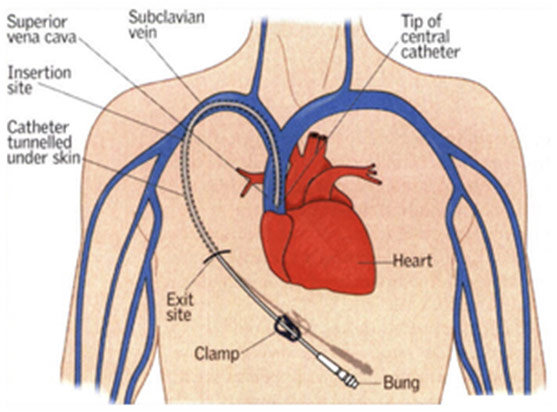

“Observe one, do one, teach one” is a common epithet heard in every residency programs around the US. Early on in his surgical residency, Dr. Gawande had to put in a central line after seeing the chief resident do two of them on her own within the first month of starting his residency. A central line is a long tube that goes into the patient’s vena cava in their heart for various different reasons, one being to give medications or fluids quickly. There are many inherent associated risks such as heavy internal bleeding, cardiac arrest, and lung collapse. You insert the needle with a syringe under the patient’s clavicle into the subclavian vein, see maroon blood filling the syringe that the surgeon subsequently removes. The surgeon then threads the guidewire through the needle and maneuvers it to the vena cava, removing the needle thereafter. After putting and taking out the dilator to expand the opening of the vein, the surgeon will finally thread the catheter in and maneuver it into the vena cava, so they can finally take out the needle. Easy right? Unfortunately, it’s much harder to do it on a real patient, and Dr. Gawande failed in doing so the first three times he tried. On the fourth time, he was successful, and he could hardly explain what he did differently. In the end, surgery is all about practice. Gawande notes that “attending surgeons say that what’s most important to them is finding people who are conscientious, industrious, and boneheaded enough to stick at practicing this one difficult thing day and night for years on end” (Gawande 19). Often, it takes forever to do something exactly right in surgery, but the only way to do it that way is to keep practicing. Eventually, Dr. Gawande came into a position where he was the one supervising a junior resident as she put in a central line in a patient. She, like Dr. Gawande before, had immense trouble setting up the central line, and every bone in Dr. Gawande wanted to take the central line and do it himself. However, she had to practice it if she ever wanted to learn how to do it. Letting a resident practice these procedures presents us with a moral dilemma that Dr. Gawande goes into great detail about: if the job is to give the patient the best possible care, then residents should never do surgeries because the attending surgeon will always give better care. However, the dilemma is that the only way to train surgeons for the future is to allow them to do surgeries under the supervision of the attending. Where this gets iffy is when people from a surgeon’s family come in for surgery because the attending surgeon will always do that surgery on his own, allowing the resident only to observe. Often, the people that residents are allowed to practice and do surgeries on without supervision are often drunk, uninsured, and poor.

Inserted Central Line

Surgery is always constantly evolving. New techniques and procedures come out, and surgeons must learn them to give their patients the best treatment possible. Nevertheless, the first few patients who receive these new techniques and procedures may not be getting the best treatment possible since the practicing surgeons themselves are learning at that point without an attending. A study done by Harvard Business School researchers aimed to study the learning curve of heart surgeons as they learned how to do minimally invasive cardiac surgery. The surgeon that was the most successful chose “team members with whom he had worked well before and [kept] them together through the first fifteen cases before allowing any new members. He had the team go through a dry run before the first case, then deliberately scheduled six operations in the first week, so little would be forgotten in between. He convened the team before each case to discuss it in detail and afterward to debrief” (29). It was not that this surgeon was the most experienced, but he was the most humble in the sense that he became a member of the surgical team rather than the de facto leader. Despite how successful a surgeon is, all surgeons consistently do make mistakes, sometimes deadly, nonetheless. Thus, most hospitals have a Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) Conference each week to discuss these mistakes and learn from them without the threat of being sued for what they share. All members of the hospital assembled here as each chief resident from various specialties came up to discuss the cases regarding their specialty. Often, this can become embarrassing for certain doctors, but it is meant to be a learning experience to improve patient care at the hospital. “No matter what measures are taken, doctors will sometimes falter, and it isn’t reasonable to ask that we achieve perfection. What is reasonable is to ask that we never cease to aim for it” and that is the lesson M&M seeks to remind doctors of (74).

Mortality and Morbidity Conference at the University of Hawai’i

Despite the mistakes, surgery has the potential to change lives for the better. Dr. Gawande has multiple examples of them in his book, but I chose two of the most interesting ones in my opinion. Vincent Caselli was a morbidly obese man at 428 pounds who owned a construction company. Dr. Gawande with the assisting surgeon Dr. Randall performed a Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) surgery on him, which works by stapling the stomach so that it becomes smaller and then connecting it to the middle part of the small intestine to bypass the first part. Thus, the patient will reach satiety even by eating extremely little, which helps them lose weight in the long term. Caselli’s obesity was affecting his quality of life: he had to sleep in a recliner chair on the first floor unable to reach his bedroom on the second floor, had to shower after going to the bathroom because keeping adequate hygiene otherwise was difficult, and had to leave his company while watching it fail without him. It was not that Caselli could not lose weight; he had trouble keeping it off like almost everyone. There was a panel that looked at various studies that showed more than nine out of ten people regained about half of the weight they lose after one year and all of it after five years. However, this surgery changed Caselli’s life. It took a while and also involved lifestyle changes, but he was able to get to 250 pounds. His quality of life improved dramatically: he finally was able to leave the house and go do things he enjoyed like seeing a Boston Bruins game and work full time, doing what he loves. He told Dr. Gawande that surgery gave him control of his life back. The next case regards Eleanor Bratton, a young woman with a swollen maroon leg that was warm to the touch. An ER doctor told Dr. Gawande that she probably had severe cellulitis, but Dr. Gawande was not convinced. One possibility, necrotizing fasciitis, popped into his mind based on a patient he had a few weeks before. This patient presented with similar symptoms and was diagnosed with cellulitis. However, his condition worsened, and he was taken from a small community hospital to Brigham and Women’s where he was properly diagnosed with having necrotizing fasciitis. Despite surgery to remove infected muscle and amputation of the arm, the patient died after all vital organs failed on him. Necrotizing fasciitis is an aggressive infection, fondly known as the flesh-eating disease. The bacteria is highly aggressive since the tissue infection spreads rapidly and cannot be treated by antibiotics alone. Early diagnosis and treatment improve prognosis, but many with the infection have some of their appendages amputated and/or die. The condition is extremely rare compared to the common cellulitis, and the general surgeon on the call said that the chance it was necrotizing fasciitis was far less than 5%. In spite of that, Dr. Gawande could not ignore the chance that it was necrotizing fasciitis. The problem was that there was no way of differentiating between cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis except for doing a biopsy. This came as a shock to Bratton and her father, both of whom reluctantly gave permission to do the biopsy. A dermatopathologist had to be called to examine the tissue, determining that Bratton indeed had necrotizing fasciitis. The general surgeon on call, Dr. Studdert, was considering doing a below-knee amputation or an above-knee amputation; however, he decided to do a debridement, which meant he took out the most infected tissue in the leg and flushed it with saline. Nevertheless, the situation was not looking good since there was a lot of infection still left because an amputation was not done, so Dr. Studdert had Bratton undergo hyperbaric oxygen therapy. This worked by putting a patient in a pressure chamber with a lot of oxygen to speed up healing since the immune system uses oxygen to fight infection. The therapy ended up working and after four more surgeries to take out the infected tissue, she ended up being discharged from the hospital. It took a while and a lot of physical therapy for Bratton to be able to use her leg again in weight-bearing exercises like jogging. She escaped probable death because Dr. Gawande shrewdly considered all the possibilities to give the life-saving early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis.

Necrotizing Fasciitis on a Patient’s Arm

Dr. Gawande writes masterfully with such thought-provoking material and great insight on it. It always keeps the reader engaged, examining cases that show some of the most interesting cases in medicine. The women who could not stop compulsively blushing, the man who had disabling back pain despite not having any associated trauma that will not go away, to the women who had hyperemesis gravidarum (severe nausea) that persisted throughout her entire pregnancy despite all kinds of intervention. I cannot do this book and the author the justice that they both deserve, and only be reading it entirely can one appreciate its authenticity and reality.

References

Ahmed, Burhan. “Central Line Placement: A Step-by-Step Procedure Guide.” Medicalopedia, 19 Nov. 2010, medicalopedia.org/161/central-line-placement-a-step-by-step-procedure-guide/. Accessed 24 Aug. 2017.

Central Venous Catheter. 28 Dec. 2014. NREMT Academy, nremtacademy.com/central-venous-catheter/. Accessed 24 Aug. 2017.

Gawande, Atul. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. New York, H. Holt, 2002.

—. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. Amazon, amazon.com/Complications-Surgeons-Notes-Imperfect-Science/dp/0312421702. Accessed 24 Aug. 2017.

Llewllyn, Tim. Atul A. Gawande, MD, MPH. Brigham and Women’s Health, brighamandwomens.org/research/labs/centerforsurgeryandpublichealth/documents/gawande%20revised%20bio.aspx. Accessed 24 Aug. 2017.

Necrotizing Fasciitis: The Flesh-Eating Disease You Want Nothing to Do With! 9 Feb. 2017. Science Vibe, sciencevibe.com/2017/02/09/necrotizing-fasciitis-the-flesh-eating-disease-you-want-nothing-to-do-with/. Accessed 24 Aug. 2017.

“Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass.” Web MD, webmd.com/diet/obesity/gastric-bypass. Accessed 24 Aug. 2017.

Scholarly Activities Sessions. Hawaii Residency Programs Inc., hawaiiresidency.org/internal-medicine-residency/scholarly-activities-sessions. Accessed 24 Aug. 2017.