For 2 weeks in August 2018, I was in Warsaw, Poland for the Gap Medics Internship. The experience was fascinating, allowing me to observe surgeries from the same vantage point as the operating doctor while also giving me the opportunity to learn so much more about medicine. My first week in Poland was spent in the gastroenterology and transplantation department while my second week was spent in the orthopedics and traumatology department. Both weeks proved especially insightful and just showed how life-changing, and hard, medicine truly is. In this post, I will be discussing three pancreatic surgeries: the Whipple procedure, distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy, and the Frey Procedure.

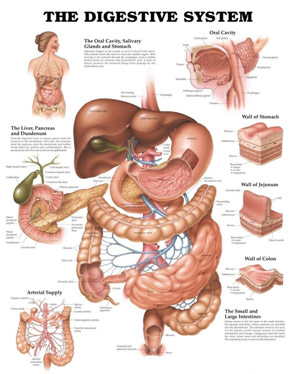

Gastrointestinal Anatomy

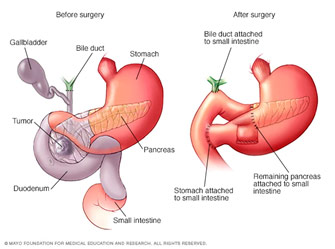

On my very first day, I walked into a pancreaticoduodenectomy, or pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure, to treat a type of pancreatic tumor in the pancreatic head. A Whipple can take several hours to complete because the tumor is in the head of the pancreas, which lies deep within the body in a critical region where the pancreatic duct and bile duct delivers their juices into the duodenum, the first section of the small intestine. The heavily invasive Whipple procedure, only done if the cancer is deemed resectable (Stage I or Stage II), sees the removal of the pancreatic head, the gallbladder, the distal bile duct, and the duodenum.

The patient was put under general anesthesia before the nurses and surgeons used betadine as an antiseptic for the abdomen. Following a midline incision (vertical down the abdomen), fascia and muscles were divided with the electrocautery while the peritoneum was divided with the scalpel to protect the intestines. After the lesser sac (space between the back of the stomach and the front of the pancreas) was opened, the surgeon released the hepatic flexure with the electrocautery to get the colon out of the way so that the duodenum and the pancreas were exposed. The Kocher maneuver followed where the duodenum and the pancreatic head were mobilized off the inferior vena cava, the vessel that takes ⅔ of the body’s blood back to the heart. After the cystic duct and the cystic artery were ligated, a cholecystectomy, removal of the gallbladder, was performed, partly because the gallbladder is hormonally dependent on the duodenum, which will be taken out in the Whipple. After the cholecystectomy, the common hepatic artery (CHA) was transected and the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) was ligated to allow for the removal of the distal bile duct. The surgeon went on then to transect the duodenum while being careful to preserve the stomach and the pylorus, the opening between the stomach and the small intestine. Afterward, the surgeon transected the pancreas at its neck to remove the head of the pancreas. In this process, he had to ligate the tributaries of the superior mesenteric artery and the superior mesenteric vein that took blood to and away from the pancreas. He then went on to divide the jejunum so that this cancerous specimen with the duodenum and pancreatic head could be removed and sent to pathology.

Following the excision of the pancreatic head, the gallbladder, the distal bile duct, and the duodenum, the surgeon began the reconstruction. The pancreas was anastomosed, or connected, to the jejunum in what is called a pancreaticojejunostomy so that the digestive enzymes made in the pancreas can still flow through the pancreatic duct into the small intestine. The common bile duct was similarly anastomosed to the jejunum, more distally, however, in what is called a choledochojejunostomy, to allow bile to enter the small intestine. More distal to both of these anastomoses, the stomach was anastomosed to the jejunum in what is called a gastrojejunostomy so that the food can still get to the small intestine despite the absence of the duodenum. An abdominal drain was kept in the patient to remove any residual blood, bile, etc. before the surgeon closes the patient up, suturing the fascia and skin tight.

Anatomy Before and After the Whipple Procedure

Divisions for the Whipple Procedure

Often, the surgeon can tell that the pancreatic cancer is not resectable if they see that cancer has metastasized (spread past the pancreas) or has infiltrated major blood vessels on imaging. Other times, however, the surgeon goes in thinking they will be doing a Whipple or another procedure but sees that the cancer is unresectable, or inoperable. In one case I saw, the pancreatic cancer was way too infiltrated with the blood vessels. The surgeon told me that the unusual bleeding that was occurring meant the patient would not even survive the operation had they continued. Thus, they simply took a fine needle biopsy before closing the patient because more surgery would have caused more harm and good. The surgeon informed me that they will try to use chemotherapy and radiation to fight and perhaps downgrade the tumor, but the patient’s prognosis was poor.

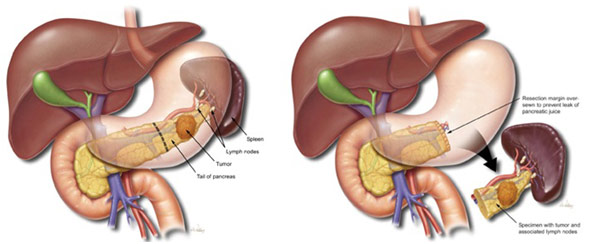

The day after the Whipple, I saw a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy where the surgeons removed the pancreas and the spleen because of a tumor in the tail of the pancreas. The surgery had a similar beginning to expose the pancreas but was not as invasive as the Whipple. The gastric vessels were ligated and various ligaments were cut to enter the lesser sac and expose the spleen. After the spleen was elevated, the surgeon dissected along the pancreas to get the neck where he used a stapler device to cut the neck of the pancreas so that he could remove the tail of the pancreas. However, before stapling the pancreas, the surgeon dissected the splenic artery and vein off the back of the pancreas and saw that he would need to remove them since cancer seemed to involve them as well. By ligating these two vessels, the surgeon made the intraoperative decision to remove the spleen at that moment because he had taken away the spleen’s blood supply. A splenectomy is not always needed as the distal pancreatectomy can be done while preserving the spleen; however, oftentimes, it is wiser to remove the spleen because it facilitates the removal of the nearby lymph nodes which may be cancerous. After stapling the pancreas, the surgeon cauterized the attachments to the spleen, allowing him to take the pancreatic tail and the spleen out of the abdomen. More sutures were used to close the stump of the pancreas to reduce the chance of leakage from the pancreatic ducts. A drain was also placed near this cut portion so that any digestive enzymes that do leak are taken out of the body.

Anatomy Before and After a Distal Pancreatectomy with Splenectomy

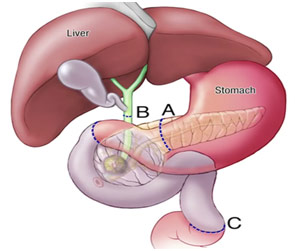

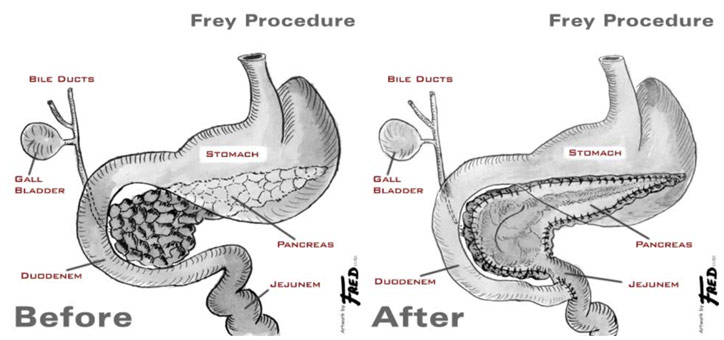

Another pancreatic procedure I saw on numerous occasions was the Frey Procedure for chronic pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis sees the inflammation of the pancreas, most often due to small stones obstructing of the pancreatic duct, which allows exocrine juices (digestive enzymes) to enter the small intestine. The condition is most often associated with alcoholism as ethanol changes the composition of pancreatic proteins to make the protein plugs that block the duct while also activating the digestive enzyme trypsin too early, which then attacks the pancreas. The trypsin and the ensuing inflammation tend to destroy the pancreatic duct. This, in turn, makes it harder for the body to digest food and increases the risk of the patient developing diabetes.

To gain access to the pancreas for the Frey Procedure, once again an incision was made, but this time it was not the vertical midline incision but a horizontal one called a bilateral subcostal incision. Like with the Whipple, the lesser sac was opened, the hepatic flexure was released, and the Kocher maneuver was performed to expose the pancreas and the duodenum. The duct of Wirsung, the main pancreatic duct through which the digestive enzymes get from the pancreas to the small intestine, was found when a syringe sucks up the exocrine juices trapped in the duct. The duct of Wirsung was then opened up and drained before all of the calculi, or stones were removed. Inflamed and damaged portions of the pancreatic head were then enucleated out. The surgeon was able to remove the obstruction of the bile duct, but if he could not, he could connect the bile duct to the duodenum (choledochoduodenostomy) or to the jejunum (choledochojejunostomy).

At one location, the omentum and small intestine were divided to help create the Roux loop, which would allow the pancreatic juices to flow into the small intestine through another way since, despite clearing the stones, the pancreatic duct may still not be patent. One end of the small intestine was tied shut and attached to the pancreas before being internally connected with it in a lateral pancreaticojejunostomy. The digestive enzymes from the pancreas now could definitely flow into the small intestine. To maintain the small intestine’s continuity, the other part of the cut small intestine (duodenum) was attached to the jejunum through an end-to-side anastomosis.

Anatomy Before and After Frey Procedure

All in all, the Gap Medics experience was one of a kind. I got such a wonderful opportunity to watch surgeries from an unbelievably close distance thanks to amazing mentors like Dr. Agnieszka. I saw surgeries done nearly flawlessly as well as surgeries with a few inadvertent complications, helping me to get a realistic picture of what medicine looks like. The experience was both rewarding and unforgettable.

References

Before and after the Frey Procedure. MUSC Health, ddc.musc.edu/public/surgery/chronic-pancreatitis/frey-procedure.html. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

The Digestive System. Scientific Publishing Ltd., www.scientificpublishing.com/product/the-digestive-system/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

“Frey’s Procedure/Lateral Pancreatojejunostomy/Dr Jitendra Mistry.” Youtube, uploaded by Jitendra Mistry, 30 Nov. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=mK_INT5MLMw. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Gap Medics Blog. Gap Medics, www.gapmedics.com/uk/blog/2017/05/17/pregnancy-myths-from-tv-infographic/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Goodman, Martin. “Whipple Procedure for Carcinoma of the Pancreas – Part 1.” Jomi, jomi.com/article/15/whipple-procedure-carcinoma-pancreas/procedure-outline. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Mayo Clinic. Whipple Procedure Divisions. Youtube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=68XsPhyMEZA&t=108s. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Nordqvist, Christian. “All about Acute Pancreatitis.” Medical News Today, 19 Dec. 2017, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/160427.php. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Venugopal, Roshni. “Pylorus-Preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure) Technique.” Edited by Kurt Roberts. Medscape, 9 Nov. 2018, emedicine.medscape.com/article/1893199-technique#c2. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Weldon, Scott. Distal Pancreatectomy. Baylor College of Medicine, www.bcm.edu/healthcare/care-centers/pancreas-center/procedures/distal-pancreatectomy-splenectomy. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Whipple Procedure. Mayo Clinic, www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/whipple-procedure/about/pac-20385054. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.