Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death, and Brain Surgery is a novel about Dr. Henry Marsh’s experience in the field of neurosurgery mostly within Great Britain from his childhood until the years before he decided to retire. Almost every single chapter begins with a name and a short explanation of a neurological disorder whose case is the primary focus of the chapter, which allowed for some spectacular learning. However, the focus of the novel as a whole is recognizing the monumental decisions that a neurosurgeon has to make and the consequences that they must deal with; it is like walking across a tightrope over a grand cavern. The book represents that pinnacle of storytelling whose candidness reveals mountains about the field of neurosurgery.

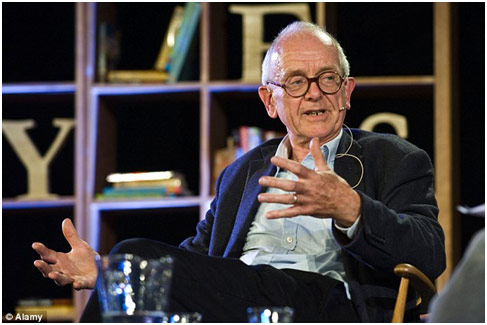

Dr. Henry Marsh

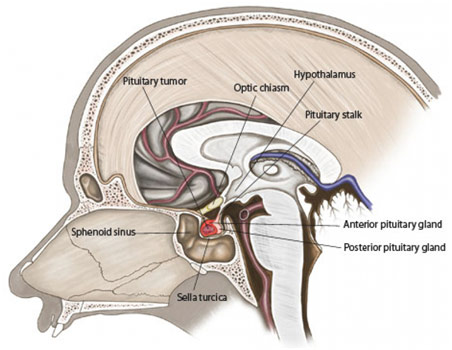

A patient is diagnosed with a right middle cerebral artery aneurysm that the interventional radiologists cannot treat, so the only treatment option is for the neurosurgeon to surgically clip it. The problem is that the risks of surgery equal the risks of doing nothing as both cases can cause a catastrophic stroke that kills the patient. This is just one of the cases that Dr. Marsh has to deal with where he did not know what was best for the patient. The patient ultimately wanted to have the surgery, which fortunately was a success despite problems with the applicator for the clip that threatened to rupture the aneurysm and cause a torrent of intense bleeding. Dr. Marsh comments that the gratification that comes from saving a patient’s life and improving their quality of life is a “deep and profound feeling which [only a] few people other than surgeons ever get to experience” (Marsh 33). However, the gratification is sometimes forgotten amidst all of the operations that inadvertently fail. This failure is not always obvious for the neurosurgeon as the patient may have survived the operation, but many a time when a patient is followed up does the neurosurgeon find them in a total disaster state from the complications of the surgery. Dr. Marsh recognizes that sometimes not operating is definitely the better choice since complications of neurosurgery can result in a case that is worse than death. Indeed, this is definitely something that is hard to tell a family who is banking on the surgeon to do something tangible. They are filled with a hopeless optimism that prevents them from accepting the truth of the matter. Thus, Dr. Marsh has sometimes operated on these impossible cases, like a woman with another recurrence of ependymoma (a malignant tumor that formed in the ventricles of the brain) who wanted a fourth surgery, despite knowing that it would do no good for the patient. Dr. Marsh recognizes that “life without hope is hopelessly difficult” for the patient and the family alike, but he also remembers that “at the end hope can so easily make fools of us all” (139). Certainly, being a neurosurgeon can drain even the surgeon’s hope since there are so much suffering and turmoil, always having one disaster after another. The worst part is that even when the surgeon does everything perfectly and makes no clear error as Dr. Marsh did for a patient with pituitary adenoma, fatal complications can still occur. That patient suffered a stroke after the operation that eventually led to his brain being coned as it was pushed through the foramen magnum (big hole in the skull that connects the brain to the spinal stem) like “toothpaste” (184). It is not the successes that Dr. Marsh remembers but the failures. It is not the patients who live healthy lives but the ones who died or were put into a state so terrible that death would have been preferred.

Diagram of a Pituitary Adenoma in the Anterior Pituitary Gland

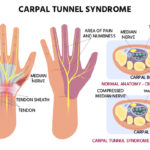

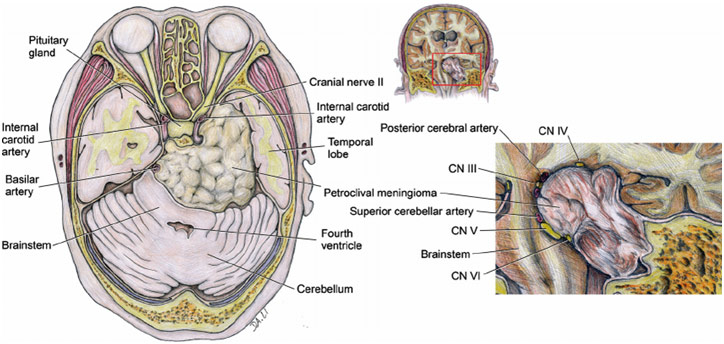

Dr. Marsh quite literally shows us the harsh reality of neurosurgery, not sugarcoating it in any way. He painfully reveals that “you only get good at the difficult cases if you get lots of practice, but that means making lots of mistakes at first and leaving a trail of injured patients behind you” as he speaks openly about his own mistakes and how they have changed him (210). One of his worst mistakes came when he operated on a man with an extremely large petroclival meningioma, whose name comes from it arising from the meninges in the petrous and clivus bone region, that covered much of the brain and threatened to compress the cranial nerve or push on the brain stem, which could have terrible consequences. Thus, the family decided to proceed with the surgery after getting a second opinion from another neurosurgeon. The operation was going really well, and most of the tumor was out without any injury to the cranial nerves. Dr. Marsh could have stopped there, but he wanted to go further and take every single part of the tumor out like the famous neurosurgeons he had seen. Attempting to do so resulted in accidentally rupturing the basilar artery, which feeds the vital brainstem, and a “narrow jet of bright red arterial blood started to pump outwards” (211). The patient was put into a permanent coma; he never woke up. Even in this memoir, Dr. Marsh was unable to put his grief and anguish into words. As the French surgeon, René Leriche once wrote, “every surgeon carries about him a little cemetery, in which from time to time he goes to pray, a cemetery of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for all his failures.” Dr. Marsh has no adequate explanation for his disasters, all of which he can never forget but can only atone for and learn from.

Diagram of a Petroclival Meningioma Compressing the Cranial Nerves

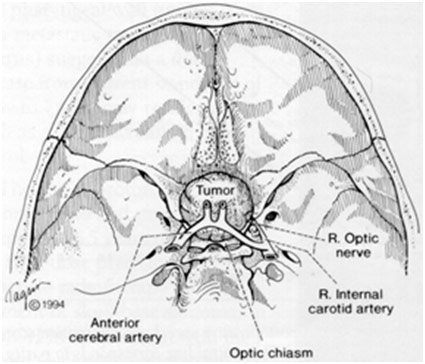

In the end, Dr. Marsh’s story is a memoir of some of his worst mistakes but also of some of his greatest successes, which are much more beautiful. For example, take the story of an anxious patient with a tumor of the pineal gland, which was causing hydrocephalus by blocking the cerebrospinal fluid from flowing like it normally should. Dr. Marsh performed the craniotomy and looked “for a narrow crevice that separates the upper part of the brain, the cerebral hemisphere, from the lower part — the brainstem and cerebellum” to reach the pineal gland (7). After a small part of the tumor was sent to pathology, the diagnosis of pineocytoma was made, and Dr. Marsh removed most of the tumor, which was not tightly stuck to the brain. In the end, the patient recovered well, and his life was transformed for the better. Additionally, take the story of a young pregnant woman with suprasellar meningioma, which was compressing the optic nerves and had the potential to cause blindness. Surgery could save her eyesight and even could restore it, so the family agreed to the surgery. Using a Gigli saw “to make a very small opening in the skull above Melanie’s right eye,” Dr. Marsh and his team removed the bone and worked his way under the brain to access the tumor by drilling the ridges of the skull flat and removing the cerebrospinal fluid with a lumbar drain, which allowed her brain to look “‘slack’ as neurosurgeons say — there was plenty of room” for his team to access the tumor under the brain (53, 54). With more work under the brain, Dr. Marsh finally exposed the optic nerve where he easily cut and removed the tumor with a suction tube until he was able to view the anatomy without any obstruction. His team quickly closed up, and the obstetricians soon delivered a healthy baby boy by C-section under the exact same anesthesia. Thankfully, Melanie recovered well as her vision soon returned, and she was actually exalted to be able to see her baby.

Diagram of Suprasellar Meningioma Compressing Optic Nerves

There is no lying when one says being a neurosurgeon is hard. It is excruciatingly difficult and painful. However, there is also no lying when one says that it can also be heartwarming. The moments when the neurosurgeon changes one’s life are the moments that in the end makes everything worth it. Dr. Marsh definitely conveyed both of those ideas to his readers with such candor, that deserves nothing but utter respect for him and his work. The book is undoubtedly a wonderful masterpiece, which can only be truly appreciated by reading the entirety, vicariously experiencing what Dr. Marsh had to go through.

References

Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death, and Brain Surgery. Barnes & Noble, www.barnesandnoble.com/w/do-no-harm-henry-marsh/1120204957#/. Accessed 15 Jan. 2018.

Illustration of the relationships between a petroclival meningioma and the surrounding neurovascular structures. Transverse section through the pons and eyeball ( left ). The lesion partially encased the basilar artery and the left carotid artery, involved the cavernous sinus, and significantly compressed the brainstem with a noticeable space-occupying effect. Research Gate, www.researchgate.net/figure/Fig-1-I-llustration-of-the-relationships-between-a-petroclival-meningioma-and-the-surrounding_267044839_fig1. Accessed 15 Jan. 2018.

Leading Brain Surgeon Henry Marsh (Pictured) Has Accused the Prime Minister of Fomenting a ‘Permanent Revolution’ in the NHS which is Demoralising Staff. Daily Mail, www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2914866/David-Cameron-s-favourite-surgeon-memoir-moved-PM-tears-tells-NHS-policy-c.html. Accessed 15 Jan. 2018.

Marsh, Henry. Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death, and Brain Surgery. New York, Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin’s Press, 2015.

Pituitary Adenoma. UCLA Health, pituitary.ucla.edu/pituitary-adenomas. Accessed 15 Jan. 2018.

Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma. Massachusetts General Hospital, neurosurgery.mgh.harvard.edu/cranialbasecenter/c94.htm. Accessed 15 Jan. 2018.