I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Renée Rodriguez Paro, a pediatric cardiologist who has dedicated much of her free time to spreading health literacy through her podcast Reconciling Medicine and her nonprofit Doctor Vegetable. With her husband and plastic surgeon Dr. John Paro, she works to make meaningful impacts on both an individual and societal level. In particular, I find her efforts to support physician wellness to be quite remarkable. On top of all her exciting work, she is a full-time mother of two as well as a fitness enthusiast and marathon runner. She is an inspiring person, and it is an honor to share her inspiring story.

What do you think are the traits of a great physician?

I think a good doctor is someone who wants to help other people, someone who has that altruistic tendency. I think it is somebody who wants to serve people and be connected to them in their most vulnerable states as well as somebody who wants to be a lifelong learner and a leader. There are lots of roles in medicine—nurses, nurse practitioners, respiratory therapists, pharmacists—and all of them are quite important. If you are interested in healthcare, understanding where within that group your personality falls is really important. As somebody who wants to be a physician, you would want to be somebody who wants to be a leader, somebody who wants to be their own boss, somebody who does not want someone else dictating what they are doing.

A good doctor is also somebody who can put another person’s needs above their own; you need to have your patients be your primary focus and do whatever you can to take care of them. Sometimes, that can lead people to then give up too much of their lives, so it is a fine balance between not over-sacrificing but also knowing that patients really do come first. Nowhere do I talk about being the smartest person in the class. I do think you need to have a certain level of intelligence, obviously, but, at the end of the day, the physicians who are the most impactful with their patients are those who can actually talk to them and communicate with them. If you are super smart but do not have the ability to actually connect with another human being, you are not going to be a good doctor.

What motivated you to specialize in pediatrics and then subspecialize in pediatric cardiology?

I had an aunt who let me be in the delivery room as an 8-year old when she had her first child. During that experience, I was captivated by the whole experience, watching the healthcare team mobilize to deliver the baby. In general, I have always been drawn to kids because my mom owned a preschool, and I was a preschool teacher for her when I was in high school. In medical school, I was choosing between obstetrics and pediatrics, but, after doing my surgery rotation, I decided on pediatrics. I knew that I did not want to do general pediatrics because it was not my passion, and I knew that I wanted to be a subspecialist of some sort. I thought I would be doing GI, or specifically hepatology because I was really interested in the liver.

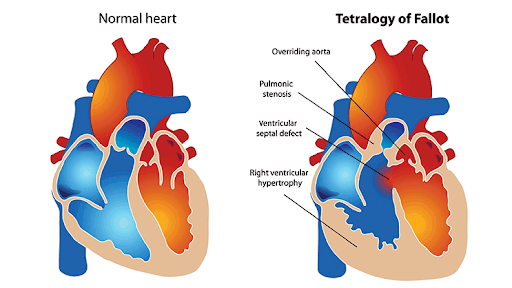

When I got into my pediatrics residency program at Stanford though, I found myself engaging with a large, well-known pediatric cardiology program, and I fell into love with it. I did pediatric cardiology as my first rotation in my residency, and I really liked the tangibility of cardiology. You can diagnose a problem and understand complex anatomy. If you want to work up a problem, you have various different modalities—echocardiography, electrocardiography, the interventional lab, exercise testing, and more. I also liked the complex physiology of congenital heart disease. It is a very interesting way of thinking about how blood flows through the heart, and the only people who really get it are pediatric cardiologists. I also really liked the people within pediatric cardiology; they are very surgically minded. Pediatricians can be a little “soft” around the edges, but pediatric cardiologists are a little more cut and dry and to the point, and I really liked that. Matching into my fellowship, I realized that I liked every part of cardiology. For some time I thought about interventional cardiology or an additional echocardiogram or ICU fellowship, but at the end of the day, I appreciated seeing a wide variety of patients and practicing outpatient medicine.

Normal Heart vs. Tetralogy of Fallot Heart, a Rare Congenital Heart Disease

Where do you see the treatment of heart disease in the future?

Pediatric cardiology is a relatively young field. Within the next 10-20 years, I think there will be greater advances in our ICU treatment strategy after kids undergo surgery as well as improvements in surgical and procedural care for kids with complex congenital heart disease. For kids that previously would have passed away early in life or would not have survived certain procedures, I think their outcomes will be better. I also think that genetic screening and the ability to tie conditions to genetic causes, such as inherited arrhythmias, will allow us to pick up heart conditions earlier on, which could be life-saving.

Something specifically I am interested in is preventative cardiology. We are starting to screen kids earlier on and more universally for high cholesterol to be able to start intervening at an earlier age with more nutritional counseling and genetic testing for cholesterol-related conditions. That prevention piece is really crucial because to have kids know early on if they are at risk and to start them on statins at a young age could help prevent them from having a heart attack 30, 40, or 50 years down the line.

What is your podcast Reconciling Medicine about and what kinds of topics do you discuss?

Reconciling Medicine is a podcast my husband and I started, and it is a discussion between two physicians who have done their entire medical training together. We met as first-year medical students, started dating our second year, got engaged our fourth year, and got married our intern year. We had our son at the end of my residency and our daughter the year after we started practice. We have really been through this whole process together as a couple, so Reconciling Medicine is a discussion of what we went through. It is meant for students as well as residents, medical students, and other physicians to better understand the different avenues and ways to progress through medicine. What we hope to get across is that while there are a large number of people who are unhappy in medicine, there is value to being a physician. When you talk to doctors, the majority of them are probably going to tell you a lot of bad things about medicine and why you shouldn’t go into it. What we are trying to say is that, yes, medicine is hard and there are things that need to be changed, but we love what we do. We want to give a positive voice to medicine without making it seem like all sunshine and roses. We want to convey that, overall, we would do it over again. We love what we do and want to make a case that, if you are being true to yourself, following a path that makes sense for you, and are taking care of yourself along the way, then you can be happy in medicine.

Some topics we have covered include our undergraduate experience, medical school, residency, early years of practice, having kids in training, our fitness routine, our meal prep routine, breast cancer awareness episode, miscarriage, etc. We call it Reconciling Medicine because, in medicine, when you are transitioning patients, you have to do something called “reconciling their medications” where you take a history of what they are taking and input their most necessary medicines. Whenever they move from a level of care, from the ICU to the floor or from the emergency room to the hospital, you have to reconcile their medications. Medicine is a part of our lives, but we have to learn how to reconcile it within our lives.

Recording the Reconciling Medicine Podcast

What is the mission of your nonprofit Doctor Vegetable and how does your nonprofit work to fulfill that mission?

Our mission of Doctor Vegetable is to promote healthy eating to kids, something they can learn at a young age and can carry with them to adulthood to eliminate the possibility of their getting acquired heart disease. Far and away, the number one cause of death in men and women in America is cardiovascular disease. If we are trying to make the most impact on mortality, hospitalization costs, etc., lowering the number of people with heart disease will have enormous benefits. We know heart disease is not something that happens overnight but something that accumulates over a lifetime. While lifestyle factors, exercise, and stress all play a role in cardiovascular disease, the biggest piece is nutrition. The goal of our nonprofit is to promote and educate children about fruits and, predominantly, vegetables to express how incorporating them into their diet in a very plentiful way will go a long way in helping reduce heart-related problems. For nonprofits, you are supposed to have a statement of what would be a world where you were not needed. The world we envision is a world where no one has acquired heart disease, something that will never happen, but our goal is to work towards that by helping kids understand how to take care of their hearts.

Our first major initiative is to create a healthy version of the Box Tops program. For elementary schools, General Mills asks parents to cut out labels on their products like cereals, granola bars, etc., and give them to their schools, which sends the labels to General Mills. They are worth 10 cents apiece, and General Mills sends money back as donations to the schools. It sounds good, but the food that General Mills is selling is terrible: sugar-laden cereals and processed foods that are completely marketed to kids but things that kids do not need. We thought, why not make a healthy version of the Box Tops program? We have kids focus on eating fruits and vegetables for a month, and they can take the sticker from the grocery store fruits and vegetables or stickers we give them to put on their own sticker sheet. Fruits are worth one cent and vegetables are worth two cents, and they collect them over a month and turn them in. We then tabulate all the results and make a direct donation to the school in the same way as General Mills. We have done one test run in our son’s school in Pleasanton for the transitional kindergarten grade, and we ended up donating $500 to the school based on just six classrooms. This month, in November, we are doing a second test run with the whole Pleasanton school. The goal is to get this into more elementary schools in the Bay Area and then the pie-in-the-sky goal is to get this program into all elementary schools in the country.

Doctor Vegetable School Outreach

Why is spreading health literacy through your podcast and nonprofit important to you?

As a physician, you want to help people and make an impact. You do that in your clinic room, and it is a really profound thing to be able to be in someone’s life and make an impact: that is what keeps people going in medicine. We live in a day and age now when we are all so interconnected through the internet, through social media, and through the beauty of technology. If you are able to write, sing, speak—do things that can actually connect with other people—and bring that to a larger scale, why would you not do that?

Both John and I are super creative and always have been, enjoying making things and connecting with other people. We have high hopes for the field of medicine despite negative overtones with the profession, and, with the podcast, we wanted to be a voice of optimism and positivity, not through putting rose-colored glasses but by saying that you can be happy and can do important things in this field.

With regard to the nonprofit, a physician’s voice also carries a lot of weight: where somebody else might be going into schools to talk about nutrition, coming from a pediatric cardiologist, it hits a little harder. We get to use all those years of schooling and training as well as the trust that people have in someone coming to talk to them as a physician to make an impact on a larger scale than just our clinic room.

What is the biggest challenge that you have faced in your career thus far?

The biggest challenge has been the times when I have, for whatever reason, lost sight of what is important to me. You want to be able to keep your hope and optimism alive, and one of the things, when you go through the long journey to become a physician, is that it can sometimes be beaten out of you. In a way, you have to be stripped down, you have to learn how to compartmentalize your emotions, you have to learn a bunch of information, and you have to become a doctor. However, you cannot lose sight of your humanity: the things that make you happy, the things that make you healthy, the things that make you, you. There is a lot of talk about burnout and high physician suicide rates, and obviously, these issues are multifaceted. But I think a large part of it is that people lose touch and stop prioritizing the parts of the lives that they value. My husband and I are so passionate about this work because we both have struggled at times during our training where we became very negative and disconnected. With both of us, in the second or third years of our residency, we hit really low points where we were mean to other people and where we stopped calling our families. It was because we were working so much, and we were not prioritizing our health, taking care of our mental space, or being connected in our marriage. We quickly reversed that and doing so made profound effects on everything else.

From this, I would just say that no matter how hard things get, you should never do something at the sacrifice of your sanity. You always have time to do the things that make you happy and balanced, and you need to keep them in your life.

Do you have any “words of wisdom” or inspiration for teenagers like myself and my peers who want to go into the medical field?

Make sure you are doing this for yourself. If you want to do medicine, the first and most important thing to identify is that this is for you and only you. It should not be to impress your parents or because medicine is something you have to do or something you should do because you are good at science. The medicine should be a calling and a passion; pursuing it should be because you cannot see yourself doing anything else. It is a long road, and you sacrifice a lot. If it is the only thing you see yourself doing, then it is worth it, but, if it is for anyone else, you are going to burnout. That is my number one piece of advice: do anything you can to verify for yourself if going into medicine is for you. If it is is not and you find out after you have been pre-med for three years, it does not matter. You are still young; find something else to do. Do not think you are so far down the path that you cannot get off of it; you can always get off.

The second thing is, if you are going into medicine for you, be patient and understand things are not going to go perfectly well, and they do not have to. You are going to have roadblocks, you are going to stumble, and you are going to fail. At the time, it might seem like the worst thing that could have ever happened, but you are going to look back and be really happy these missteps happened because these instances teach you something about yourself. No path is linear. No matter what you think, every single physician has struggled in their path, and, if they tell you they have not, they are lying to you. It is a commonality to have disappointments and setbacks. To get up from that makes you stronger in the end. So keep going, just keep going.

References

Normal Heart Vs. Tetralogy of Fallot Heart. Columbia Surgery, columbiasurgery.org/news/adult-congenital-heart-disease-meeting-next-generation-challenges. Accessed 3 Nov. 2019.

Paro, Renée. Dr. Vegetable. 1 Nov. 2019. Instagram, www.instagram.com/p/B4VH-KgByhm/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2019.

—. Reconciling Medicine Podcast. 4 Oct. 2019. Instagram, www.instagram.com/p/B3NU2rIBNOo/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2019.

—. Renée Marie Rodriguez. 16 Sept. 2019. Instagram, www.instagram.com/p/B2e8OfwBA9z/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2019.