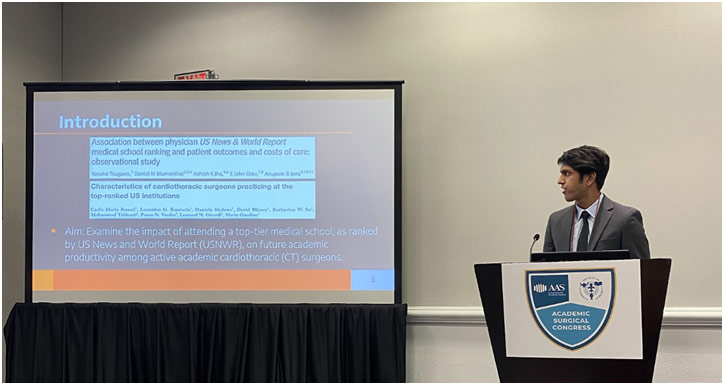

I had the great pleasure of attending the 15th annual meeting of the Academic Surgical Congress (ASC) in Orlando, Florida to present my research “Cardiothoracic Surgeons Who Attended a Top-Tier Medical School Exhibit Greater Academic Productivity” as an oral presentation. With a team at the Stanford Cardiothoracic Surgery Department, we made a database of all academic cardiothoracic surgeons in the US and found that attending a top-25 U.S. News & World Report medical school is correlated with greater academic productivity, but these differences can be ameliorated by publishing at least three papers during surgical training. One of the implications of our study was that medical schools may consider adding research opportunities to stimulate early academic productivity and those training institutions may consider enhancing their research curriculum to support trainees who may not have the same early research exposure as others. However, in this first part of a two-part series, I want to discuss an informative session I attended called “How to Write a Manuscript That Journals Can’t Say No To.”

Presenting my Abstract as an Oral Presentation

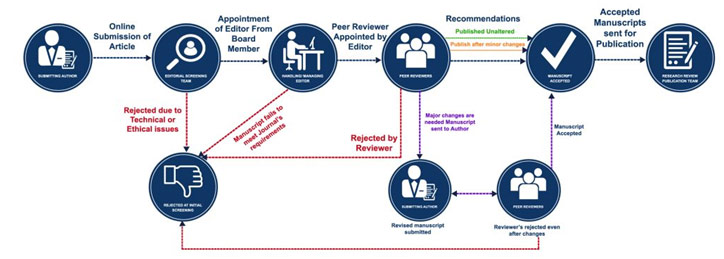

Dr. Scott LeMaire, the editor of the Journal of Surgical Research (JSR), gave a talk about what happens to the manuscript when the authors click submit. For JSR, the manuscript is assigned to a managing editor, who assesses if the manuscript is a fit with the journal and meets the journal’s basic requirements. If so, the manuscript is assigned to an associate editor who is familiar with the subject matter of the manuscript and the reviewers in that field. At this stage, poor writing, copied material, limited novelty, or a flawed design can lead the associate editor to reject the manuscript without review. However, if the manuscript is truly impactful and of quality, then the associate editor will send invitations to reviewers, aiming to get at least two looking at the manuscript. These reviewers critique the manuscript, evaluating its issues, and offering recommendations. The associate editor will then look at the manuscript in the context of the reviewers’ comments and decide whether to offer revisions or reject the manuscript entirely. The manuscripts might come back with minor revisions where the authors will make quick changes and resubmit for the associate editor to reevaluate alone, or the manuscript might come back with major revisions, which require more thorough changes and will be reevaluated by the original reviewers. At this stage, it is incredibly important for the authors to respond to every single one of the reviewers’ recommendations and, as a result, make substantive changes to the manuscript. There may be multiple cycles of revisions before the manuscript finally gets accepted if it eventually even gets accepted. If accepted, the manuscript goes to the managing editor, the publisher sends the author’s proofs to look over, and the manuscript is finally published for public consumption.

Potential Life Cycles of a Manuscript

Dr. Rebecca Spiel, the associate editor of endocrine surgery for JSR, then talked about how to make the reviewers happy with a manuscript. The thing is that the reviewers hold the key to the manuscript’s ultimate publication or lack thereof, so it is paramount to understand what exactly the reviewers want and make their life as easy as possible so that they are more likely to recommend acceptance. First and foremost, this involves carefully reviewing the “instructions for authors” that each journal provides because those are simple formatting technicalities that really irk reviewers if not followed. It is also important to follow a standard format where, for example, the last paragraph of the introduction is the hypothesis and the first paragraph of the discussion is a summary. Paying attention to the details is also especially important because the little errors in the manuscript, such as a miscalculated percentage or writing the wrong journal in the cover letter, indicate sloppy research. The manuscript should also be short and simple, being concise and to the point. If the reviewer cannot express the take-home message of the manuscript after reading it, then the manuscript is highly problematic. As a result, it is imperative for authors to clearly discuss the implications of their research—what new knowledge is gained, how this will change someone’s practice, how this will improve care, etc. The references should also be relevant, appropriate, and discussed respectfully because the reviewers have likely published in the field and will know the references you cite or have written the publications you cite themselves. Implementing all of these recommendations can go a long way towards making the reviewers more happy with the manuscript and thus more likely to recommend accepting the manuscript.

Dr. Jussuf Kaifi of the University of Missouri then talked about how to frustrate reviewers. First off, it is important to understand their perspective. These reviewers are often investigators themselves who are providing a critical service to the community. They are often doing this work late at night after completing all their other work and are not compensated for doing peer reviews, only receiving a professional honor. Given this perspective, first impressions truly matter to these reviewers because it develops within seconds of looking at the manuscript, dominating later judgment. As a result, good manuscript appearance with regards to formatting, grammar, typography, and abbreviations is paramount. Getting help from experienced writers goes a long way in this regard as well. Scientists also dislike causative language and much rather prefer passive, non-causative language because the latter does not overstate conclusions. It is the difference between “due to higher humidity wound infection cases also increased” and “as humidity increases we observed that the rate of wound infections also increased.” The former implies a causative relationship while the latter is more explicitly correlative.

Reviewers will then give feedback for the author to address. The author’s response letter needs to be easy to read, have a polite tone, and come with an introductory summary statement of changes as well as complete, point-by-point responses to the reviewer’s comments. There is an important maxim here: if the reviewer is not right, that does not mean the authors are right. For example, there may be a clarity issue at hand that needs to be addressed: “We apologize that this part was not clear… We have revised the contents of this section on page…” In addressing critiques, authors should also avoid personal reasons for why they are not making suggested changes, such as a lack of funds or a lack of time because it annoys the reviewers who do not really care about the author’s personal challenges. Critiques should also be addressed professionally, and the comments should not be taken personally. The reviewers are assessing the paper, not the authors.

Cartoon of the Peer Review Process

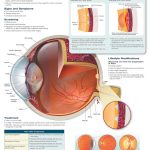

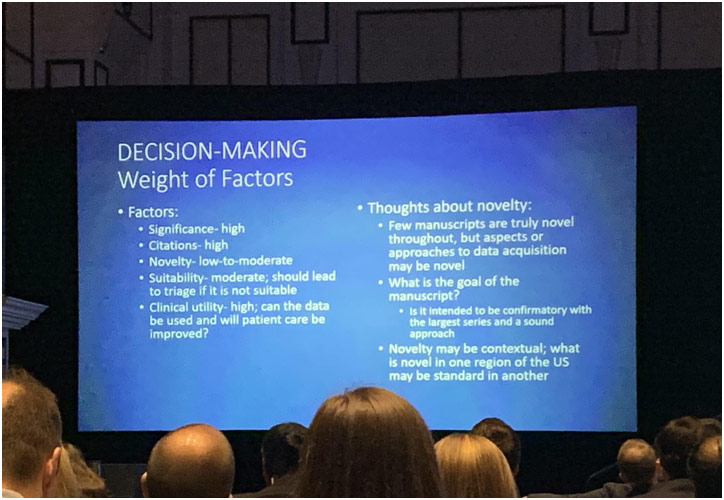

Dr. Kevin Behrens, the editor of Surgery, talked about how he makes a decision of whether to ultimately accept or reject a manuscript. The editor generally has a list of options: accept the manuscript (<2%), accept with minor revisions with no re-review (3-5%), accept with major revisions with re-review (10%), give major revisions with no guarantee of acceptance (25%), or reject (60%)—these percentages are for Surgery in particular. The editor’s job is to study recommendations and comments from reviewers, reading the entirety of the manuscript if there are favorable reviews, before making an initial decision. If there are mixed reviews, the editor looks to the depth and quality of the reviews while also taking into account the track records and strength of the reviewers themselves. Upon getting revisions, the editor is responsible for reevaluating the manuscript with the original reviewers and making the final decision. The decision comes down to the significance of the manuscript, the potential citations it might lead to, the novelty of the manuscript, the strength of the data and approach, the suitability of the manuscript for that journal and its readership, the scope of the research, and the clinical utility of the manuscript. These factors make the difference between acceptance and rejection.

Factors Dr. Behrens Takes into Account When Deciding a Manuscript’s Fate

Attending ASC was a spectacular experience for me to learn more about medicine at the highest level through informative sessions filled with impactful presentations. It was such a privilege to be able to attend this national surgical conference as a high school student, and I truly enjoyed every moment of it.

References

Allen, Annette. A Minority Peer Reviewers Are Overworked. 23 Nov. 2016. Vox, www.vox.com/science-and-health/2016/11/23/13713324/why-peer-review-in-science-often-fails.

Farma, Jeffrey. Welcome to the 15th Annual Academic Surgical Congress. 4 Feb. 2020. Twitter, twitter.com/jeffreyfarma. Accessed 15 Mar. 2020.

Peer Review at Research Review Journals. Research Review Journals, rrjournals.com/peer-review-process/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2020.