Ever feel like you cannot let go. You have put in too much time, too much work, and too much money. A little more cannot hurt: after all, you do not want to waste. When you tell yourself that, you are succumbing to the sunk cost fallacy, which is when people forget that there is nothing they can do to recover their losses. They throw good money after bad, failing to remember that their losses do not need to affect their current decisions. Clearly, this holds enormous implications for doctors as they may fail to pursue different treatments or negatively change their course of action based on the unimportant information.

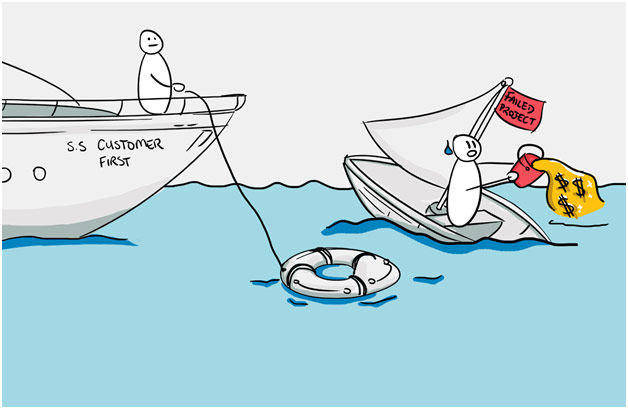

Illustration of the Sunk Cost Fallacy

Arkes and Blumer described an experiment that proved how problematic the sunk cost fallacy can be from a non-medical standpoint. In the study, students had to assume that they had bought two ski trip tickets: one for $50 and another for $100. However, they soon find out that both trips are on the same weekend, so they must choose one and waste the other. The researchers then told them that they would probably enjoy the $50 trip more. Despite this, more than half of the students chose the $100 despite knowing that they would not enjoy it as much. Simply stated, this is because of our inherent loss aversion system that forces our minds to try to try to ensure that we waste the least amount of money possible. Ideally, these students should realize that their $150 is gone no matter what they do, so they should choose the option that they will enjoy more. This point is furthered in another example regarding restaurants. Have you ever finished a meal at a restaurant despite being absolutely full? The answer for most people would be yes since they feel an obligation to finish the meal as they had spent a good sum of money on it. However, this is the textbook definition of the sunk cost fallacy since this lost money is influencing their future decisions. They are choosing to continue eating, which may cause them to feel sick, instead of walking away, happy, and content, which is far preferable. Although, the sunk cost fallacy has more serious implications than your worries of some wasted money as it is what encourages governments to keep fighting a losing war since they have put so many resources in the past. It is what makes companies reluctant to leave huge failing projects. It is what causes doctors to make bad decisions.

Quote Regarding the Sunk Cost Fallacy

Doctors often fall suspect to this kind of fallacy, whether it be in the clinic or in a research lab. For example, doctors sometimes get so caught up in their pursuits that results disproving their hypothesis are viewed with skepticism. Instead of accepting this loss of time and effort and starting over, they keep redoing their entire experiment, hoping that this hard work will not go to waste. Not only does this encourage a false interpretation of results to make this sunk cost worth it but it also causes even more waste of time and effort to try to prove something that cannot be proven. Similarly, doctors may feel disinclined to discontinue a treatment that has already been deemed as ineffective since they have spent so much time and effort on it. In fact, a study by Braverman and Blumenthal-Barby in the journal Social Science & Medicine found that around 10% of clinicians would do just that. Of course, this is detrimental to the patient since they are not getting the most beneficial treatment, which greatly endangers their health and well-being. Additionally, when the situation was described to have a large investment of the provider’s time and a large amount of the patient’s money, they were more likely to continue treatment than if there was no investment. Thus, the sunk cost fallacy is a large problem, which can dramatically influence doctor’s decisions. In a separate article by Eisenberg, Harvey, Moore, Gazelle, and Pandharipande in the journal Radiology, the sunk cost fallacy was discussed in regards to two patients and a CT exam for possible appendicitis. The paper began by going over how CT exams have been more scrutinized in recent years since they are often used, even when they are not necessary. The authors further described how CT exams have led to deaths due to cancer since they expose a person to radiation. With this introduction, the paper delved into the thought experiment where two patients present with abdominal pain and are identical except patient B had testicular cancer. Thus, patient B has had a lot more radiation exposure than patient A. The logical option would be to give them both CT exams; however, the sunk-cost fallacy forces us to consider patient B’s radiation exposure history and make us feel more reluctant to give patient B another CT. This seems illogical since each radiation exposure independently risks cancer, meaning that history is irrelevant as one more CT exam has the same probability of causing cancer in either patient. As Eisenberg et al. put it, “only the risk of the current CT examination should be considered in this risk-benefit analysis. A decision against an additional CT examination will not reduce the cancer risks—sunk costs—-incurred with previous examinations” inpatient B. In other words, the radiation from the other exams is irreversible and should not influence whether another CT exam is done. If the benefit for patient A is greater than the risk of the CT, then the same should be true about patient B, which means both patients should get a CT exam. In an ideal world, this would be true, but patient radiation histories are increasingly influencing doctor’s decisions as they are being integrated into the computer system, which is a warning against another CT in some cases. Thus, the sunk cost fallacy is a major pitfall for health care workers, who must remember to not place emphasis on things that cannot be recovered.

Acute Appendicitis on CT scan with phlegmon formation in right lower abdomen

The sunk cost fallacy plays a huge role in medicine and other professions alike and is often hard to not fall for; however, it is imperative not to succumb to our natural tendency to bog ourselves down with irrelevant information. It is imperative to remember what is important and what is not since these sunk costs do influence clinical decisions, often negatively. We must remember that the extensive resources spent on a research project should not cause us to ignore the results and to keep retrying the experiment. We must remember that your time and your patient’s money should not influence whether a patient continues an ineffective treatment. We must remember that a patient’s past CT history does not change the risk of having another CT. If a doctor is able to do all of that and not fall susceptible to the sunk cost fallacy, then they are definitely doing something right.

References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3359514/#r14

https://www-sciencedirect-com.puffin.harker.org/science/article/pii/S0277953612002407

Braverman, Jennifer, and J.S. Blumenthal-Barby. “Assessment of the Sunk-cost Effect in Clinical Decision-Making.” Social Science & Medicine. ScienceDirect, www-sciencedirect-com.puffin.harker.org/science/article/pii/S0277953612002407. Accessed 27 Dec. 2017.

Eisenberg, Jonathan, et al. “Falling Prey to the Sunk Cost Bias: A Potential Harm of Patient Radiation Dose Histories.” NCBI, 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3359514/#r14. Accessed 27 Dec. 2017.

McRaney, David. “Survivorship Bias.” You Are Not so Smart: A Celebration of Self Delusion, 23 May 2013, youarenotsosmart.com/2013/05/23/survivorship-bias/. Accessed 27 Dec. 2017.

Mean #Business – Don’t hang on to a mistake just because you spent lots of time making it. Pinterest, www.pinterest.com/pin/13792342588221648/. Accessed 27 Dec. 2017.

Sunk Cost Fallacy – Are Your Assets a Liability? The Customer Experience Company, customerexperience.com.au/2016/09/04/sunk-cost-fallacy-assets-liability/. Accessed 27 Dec. 2017.