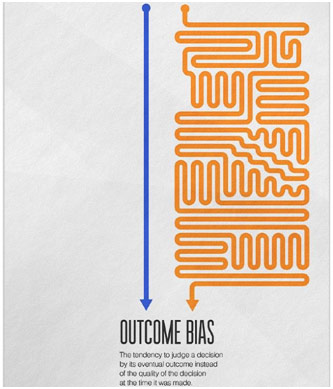

We have all heard the deontological argument that the ends do not justify the means. Outcome bias is based on the notion that the ends do not necessarily say anything about the means. All too often, we as humans tend to give excess importance to the outcome rather than the method through which the outcome was produced. The quality of the outcome begins to dictate the quality of process: if we get a good outcome, we consider our process good; if we get a bad outcome, we consider our process bad. While evaluating methods based on their outcome certainly has its place in life and even in medicine, outcome bias can lead to faulty research and improper patient care, both of which can have deadly consequences.

Outcome Bias

It first helps to understand some nonmedical examples of outcome bias. In sports, a player might score a goal, make a basket, or win a point, but do so in an inefficient manner. However, the player continues this unsustainable methodology because it provides them a satisfying outcome. In the long run, the player may be sidelined by injury or be unable to deliver when the stakes are the highest. Similarly, a gambler might hold onto one experience making thousands of dollars at the slot machine to justify throwing more money down the drain in a casino. All too often, a favorable outcome leads us to continue a poor process. While the consequences in the short term may not be especially severe, the long term sees outcome bias as its most devastating.

Another Nonmedical of Outcome Bias

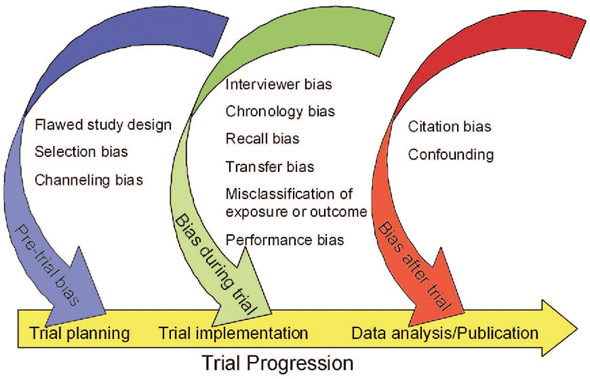

In research, outcome bias can be quite devastating by lending credence to a poor study. The rule in research is to always look at the procedure before looking at the results because the results are only as good as the procedure. When we get blinded by the seemingly remarkable results, we neglect to perceive the bias or the systemic errors present throughout the experiment. A paper in Cell Metabolism discussed how grizzly bears manage to avoid diabetes during hibernation by turning off the protein PTEN in their fat cells. The implications of these results towards preventing diabetes were spectacular, but the paper had to be retracted when it was discovered that some of the data were falsified. Similarly, when drug companies sponsor their own research, it is paramount to be aware of potential bias rather than just enthusiastically accepting their notable results. For example, the study may have had a suspiciously restrictive exclusion criterion, or there may not be any evidence to suggest that the drug itself is responsible for the benefit to the patient. Furthermore, the benefit may even be minimal at best. To avoid outcome bias in research, we must always critically evaluate the procedure to determine what, if any, credence should be given to the results, no matter how revolutionary the authors tell us they are.

Major Sources of Bias

Of course, outcome bias plays a detrimental role inpatient care as well. There is a common medical aphorism, “If you hear hoofbeats in Texas, think of horses, not zebras.” Basically, the more common diagnosis is likely the correct diagnosis. However, every so often, the zebra, or rare diagnosis, proves to be correct. For example, instead of testing for the common skin infection cellulitis, the physician orders a biopsy and discovers that the patient has a much more serious necrotizing fasciitis or flesh-eating disease. The physician thus is able to save the patient and recounts this “great catch” for years to come, using this beneficial outcome to always justify their gut feeling. Despite that case being the exception to the norm, the physician begins to carry out a biopsy for every patient that has cellulitis, leading to a great deal of unnecessary care, which brings with it its own medical risks and burdens on healthcare costs. Furthermore, the physician so caught up with finding a zebra may even begin to miss the horses. One great outcome detrimentally clouds the process for countless other patients.

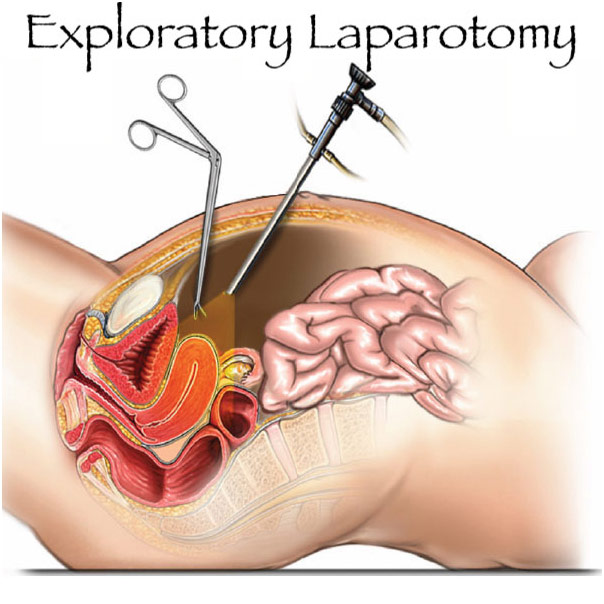

However, the problem with outcome bias also works the other way. A physician may recommend a patient with unexplained abdominal pain to go in for an exploratory laparotomy, but the patient may die on the table during the surgery. The terrible outcome in this scenario can cause physicians to begin shying away from giving other patients the research-based standard of care, fearing the potential risks. The physician may avoid recommending surgery for other patients with unexplained abdominal pain despite the necessity of this surgery to save these lives. The fact of the matter is that every treatment and every procedure in medicine comes with its risks, and every so often these risks, unfortunately, do materialize. However, allowing one poor outcome to have the physician reject the standard of care, to forget that the benefits outweigh the risk when the procedure is indeed indicated, can be extremely detrimental to other patients in the long run.

Exploratory Laparotomy

Baron and Hershey published a study regarding outcome bias where they gave students various medical scenarios with only a few differences. For example, a physician recommended a 55-year old man to go ahead with a bypass operation for his heart problems despite an 8% chance of death from the operation. What they found was that the student’s evaluation of the physician’s decision was significantly more favorable given a positive outcome and significantly more critical given a negative outcome. The only difference between these two scenarios was if the patient survived or died. While outcome bias affects researchers and physicians, the effect on patients is perhaps unparalleled. To a family, the fact that 92% survive a bypass operation does not give much comfort if their family member is among the 8% who die. Avoiding outcome bias is not about neglecting these poor tragic outcomes. Rather, avoiding outcome bias is not allowing the outcome, whether it be good or bad, to bias one’s thinking about the quality of the process. It is about rationally separating the two unless evidence suggests that they are indeed linked.

REFERENCES

Armitage, Hanae. “Falsified Data on Grizzly Bear Study Leads to Paper Retraction.” Science Magazine, 2 Sept. 2015, www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/09/falsified-data-grizzly-bear-study-leads-paper-retraction. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Cancer Patient. Time, time.com/5548593/police-cancer-patient-marijuana/. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy. HMT Hospitals, hmtsanctamaria.org/treatments/other-pro/. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Freedman, David. “Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science.” The Atlantic, Nov. 2010, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2010/11/lies-damned-lies-and-medical-science/308269/. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Hagley, Jack. Outcome Bias. Interaction Design Foundation, www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/outcome-bias-not-all-outcomes-are-created-equal. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Halton, Clay, editor. “Outcome Bias.” Investopedia, 19 July 2019, www.investopedia.com/terms/o/outcome-bias.asp. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Jones, Clay. “Outcome Bias in Clinical Decision Making and the Assessment of Our Peers.” Science-Based Medicine, 5 Dec. 2014, sciencebasedmedicine.org/outcome-bias-in-clinical-decision-making-and-the-assessment-of-our-peers/. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Major Sources of Bias in Clinical Research. Semantic Scholar, www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Identifying-and-avoiding-bias-in-research.-Pannucci-Wilkins/8d67ca95ebde06f38cf0d1b6e0e256b6d5c8b90c/figure/0. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Outcome Bias. Medium, medium.com/coffee-and-junk/cognitive-bias-outcome-bias-738ab4dc8f20. Accessed 20 July 2019.