At the age of 36, Paul Kalanithi was diagnosed with Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer, a devastating disease with a 6% five-year survival rate. However, Kalanithi was also a physician in his final year of neurosurgical training; with his diagnosis, he saw his entire future, his chance at a better life for himself and his wife, vanish before his eyes. Written while he bravely battled his cancer, Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air discusses mortality, the blurred lines between life and death. While Kalanithi’s death at age 37 meant his book had to be completed posthumously, the book serves as a reminder that, in the face of impending death, we must carry on living

Dr. Paul Kalanithi with His Daughter Cady

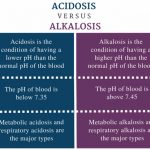

After earning bachelor’s degrees in English Literature and Human Biology at Stanford, as well as a master’s degree in the History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine from the University of Cambridge, Dr. Kalanithi went to Yale School of Medicine because healthcare offered this perfect convergence of his varied interests. One of the most remarkable aspects of Dr. Kalanithi’s time at Yale was spent doing cadaver dissection: he claimed that “cadaver dissection epitomizes, for many, the transformation of the somber, respectful student into the callous, arrogant doctor” (Kalanithi 44). Cadaver dissection represents such a monumental stepping stone in the making of a doctor because the literal act of cutting open another human being makes us feel as if we are crossing a boundary that is best left uncrossed. However, the callousness Dr. Kalanithi mentions comes from how the previously meaningful cadaver dissection becomes routine as students begin to objectify the dead, reducing the human to tissues and organs. He writes that “in our rare reflective moments, we are silently apologizing to our cadavers, not because we sensed the transgression but because we did not” (49). In doing what became a mere academic exercise, Dr. Kalanithi found himself and his peers losing sight of the humanity intrinsic to medicine.

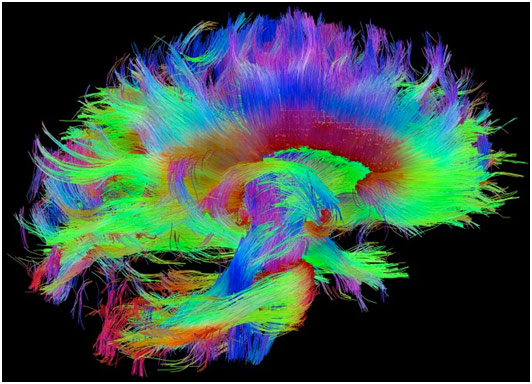

While at Yale, Dr. Kalanithi chose to go into neurosurgery, one of the most demanding specialties in all of medicine. He was attracted by the philosophical implications of the field because the question in neurosurgery is not always life or death: the gray zone exists in what kind of life is worth living. What are you willing to sacrifice? What matters to you? In operating on the “crucible of identity,” neurosurgeons “manipulat[e] the substance of ourselves,” and Dr. Kalanithi found that carrying the burden of discovering a patient’s values extremely meaningful (71). However, he also plainly called neurosurgery an awful job. After all, the pay is not commensurate to the years of schooling and high level of competency required, the work hours are incessant and unforgiving, and death is an inevitable, recurring aspect of the job. Nonetheless, Dr. Kalanithi chose neurosurgery because he was not looking for a job: to Dr. Kalanithi, neurosurgery was his calling. He simply asserted that “you can’t see it as a job, because if it’s a job, it’s one of the worst jobs there is” (151). When his graduating class at Yale was rewriting their commencement oath, some wanted to remove the idea that doctors put their patients above themselves, which, while completely rational, “struck [Dr. Kalanithi] as antithetical to medicine” (68). He saw medicine as a calling to serve humanity, something that mandated service beyond oneself and one’s own self-interests.

Cadaver Dissection Lab

Interestingly enough, Dr. Kalanithi did not believe in saving all lives: “learning to judge whose lives could be saved, whose couldn’t be, and whose shouldn’t require an unattainable prognostic ability” (80). Indeed, based on the patient’s values, some fates are worse than death. The problem, Dr. Kalanithi contends, is that neither the physician nor the patient’s family has the full picture. The doctor does not know all the past happy memories the family is reminiscing in while the family does not know the dismal future of “pasty liquid dripping through a hole in the belly” for the patient (87). The goal for the surgeon then becomes to bring together those two perspectives and the patient’s values in order to make the best decision. In residency, Dr. Kalanithi’s goal was never to save the most lives as he knew death would always win in the end; his goal was to help guide families through death with his words when a scalpel could do nothing more. Dr. Kalanithi admits that the secret to being a good doctor is to know “that the deck is stacked, that you will lose, that your hands or judgment will slip, and yet still struggle to win for your patients” (115). Medicine often comes down to these split-second judgment calls where life and death hang in the balance, and Dr. Kalanithi hoped residency would give him the wisdom to make the right decisions. Perfection is impossible, but it is what doctors must constantly fight towards.

Dr. Kalanithi was also acutely conscious of the humanity of medicine, something that the rigors of residency can sometimes beat out of you. Drowning in the horror of relentless, suffocating death, he acclimated, but doing so meant separating himself from the suffering. He feared that he was “becoming Tolstoy’s stereotype of a doctor, preoccupied with empty formalism, focused on the rote treatment of disease—and utterly missing the larger human significance” (85). Thus, before every operation on a patient’s brain, the seat of their consciousness, he sought to understand the patient and their values because the cost of failure here was just too high. He sought to do better, to always make time to, for example, assuage a scared patient’s concerns and help them make the best decision for themselves. It is about treating people as people, not problems.

The Seat of Consciousness

In medicine, we tend to, unconsciously or not, separate the doctor from the patient, the shepherd from the sheep. In many ways, When Breath Becomes Air is so memorable because it offers this perspective of a physician undergoing terminal illness.

I received the plastic arm bracelet all patients wear, put on the familiar light blue hospital gown, walked past the nurses I knew by name and was checked into a room—the same room where I had seen hundreds of patients over the years. In this room, I had sat with patients and explained terminal diagnoses and complex operations; in this room, I had congratulated patients on being cured of a disease and seen their happiness at being returned to their lives; in this room, I had pronounced patients dead (16).

The role reversal was something that struck Dr. Kalanithi especially forcefully. Indeed, one of the original definitions of the word “patient” reflects the idea that a patient is something to which things happen to. This loss of agency caused Dr. Kalanithi to feel disoriented and confused, trying to navigate a terminal illness as a patient but also as a doctor. He had spent his life guiding patients through surgeries and conditions that teeter between life and death only to be put in a similarly compromising position. When his dad told Dr. Kalanithi that he was going to fight the Stage IV cancer and win, Dr. Kalanithi remembered how many times he had heard that same line before. Everyone thinks they will beat the odds, but, of course, Dr. Kalanithi knew that not everyone does. With all his medical knowledge, Dr. Kalanithi openly questioned what hope was: was it being that statistical anomaly, surviving “just above the measured 95% confidence interval?” (135). That unrelenting question was exacerbated by his oncologist’s continuous refusal to give him a specific prognosis. She did so not only because she honestly did not know but also because patients do not need scientific knowledge to address their fears; instead, they need to discover their “existential authenticity,” their values (135). Dr. Kalanithi needed to discover what gave his life meaning for himself.

After an initial period of near remission, Dr. Kalanithi’s cancer forcefully recurred and only then did his oncologist finally give Dr. Kalanithi a specific prognosis: five good years. However, she told him this prognosis “without the authoritative tone of an oracle, without the confidence of a true believer. She said, it instead, like a plea”; Dr. Kalanithi reflected that “doctors, it turns out, need hope, too” (193-94). No longer was his doctor the self-assured shepherd leading the fearful sheep but his friend, standing by his side, pleading for more. Doctors are human too; death hits them hard every single time.

Staring into the Abyss of Death

In spite of his terminal cancer diagnosis, Dr. Kalanithi worked himself towards going back to the OR and resuming his neurosurgery residency, eventually even completing it. In spite of knowing of his impending death, he chose to have a child. He saw his cancer diagnosis as simultaneously changing everything and nothing: “before my cancer was diagnosed, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. After the diagnosis, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when” (131-32). However, he refused to let himself give in to death; as long as he was alive, he would keep on living. Someone asked him if having a child so close to his death would make saying goodbye harder, and he simply replied, “Wouldn’t it be great if it did?” To Dr. Kalanithi, life was about striving, and the 8-month-year-old Cady he left behind gave him a reason to strive and live. She gave his final days unadulterated happiness that desires nothing more. The entire book is a memoir dedicated to his daughter; the book is something for Cady to remember her father by because he could not be there for her as she grew up.

REFERENCES

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html