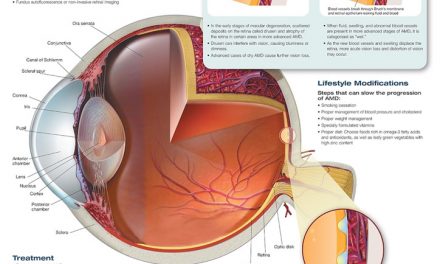

Alzheimer’s Disease affects over 5 million Americans, costing, along with other dementias (diseases that cause neurocognitive decline), the nation over $300 billion. To understand how Alzheimer’s affects the body, it is first important to have a basic understanding of the nervous system. Individual neurons receive information from dendrites, and, if the stimulus is strong enough, these neurons conduct the electrochemical signal to the next neuron. Neuronal information is primarily integrated into the brain, subsequently producing a response, again conducted through neurons. The proper functioning of these neurons is thus paramount for our bodies to be able to sense, integrate, and react to the changing world around us. In 1906, Dr. Alois Alzheimer, the disease’s namesake, dissected the brain of a patient who died of an unusual neurodegenerative disease, finding “abnormal clumps” and “tangled bundles of fibers.” Those beta-amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles, respectively, are indicative signs of Alzheimer’s, interfering with properly functioning neurons.

Neurons with Beta-Amyloid Plaque

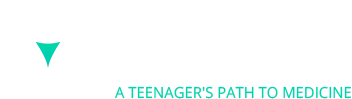

Alzheimer’s is characterized by neurocognitive decline, most prominently manifesting itself in memory deficits. The hippocampus, the structure within the brain devoted to memory, is damaged early on in Alzheimer’s patients, leading them to have trouble remembering where they put their keys or repeating things in conversations, for example. As the disease progresses to the parietal lobe, problems with spatial relationships arise with the person having trouble going up the stairs or driving, for example. Progression to the left hemisphere, the “talking” hemisphere, can cause language issues as patients start having problems with conversation, unable to find the right word. As the disease progresses to the frontal lobe, patients experience changes in their personality, for example becoming more easily upset and having less interest in general, as well as have problems with decision-making, judgment, and planning. In general, the brains of Alzheimer’s patients are significantly smaller and more shrunken than healthy brains because of the brain atrophy that comes from the disease. But what causes Alzheimer’s?

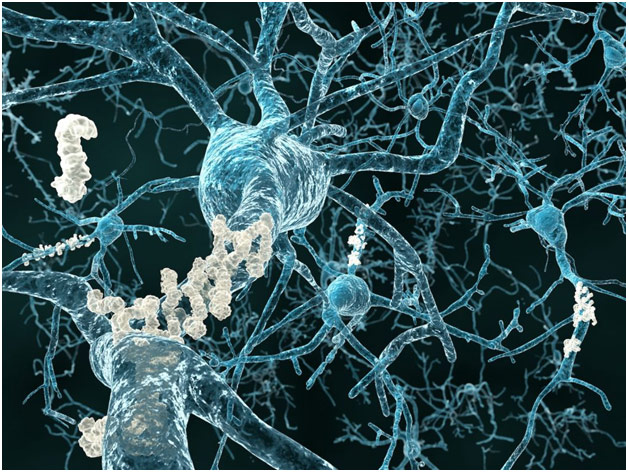

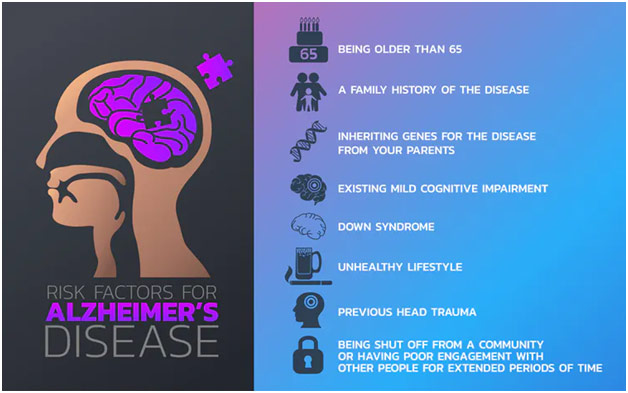

While the exact cause of Alzheimer’s is poorly understood, the disease likely originates due to a constellation of factors. For one, the genetic component of Alzheimer’s primarily has to do with beta-amyloid plaque. The normal function of amyloid precursor protein (APP) is to be cut up into parts, one of which can be beta-amyloid under certain circumstances. These toxic beta-amyloid fragments subsequently collect and block neuronal communication, causing the immune system to destroy the brain cells through monoclonal antibodies. While there are three autosomal dominant mutations that cause Alzheimer’s, including mutations to the Presenilin 1 gene, Presenilin 2 gene, and the amyloid precursor protein gene, the result of all these mutations is increased beta-amyloid in the brain, which almost ensures the person will develop Alzheimer’s. However, these mutations only explain 1% of Alzheimer’s cases and do not explain the connection to tau protein. Tau protein normally supports the creation of microtubules, which move nutrients through neurons, but, in Alzheimer’s, the tau proteins collect and collapse into tangles that cut off the nutrient flow and block neuron-neuron communication, leading to further brain cell death. The environmental aspect of Alzheimer’s is related to aging as developing the disease is quite rare below the age of 65 (early-onset Alzheimer’s; 5%) and incredibly more rare below the age of 50. Every five years after 65, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s doubles, and over 30% of American adults over 85 have the disease. Dr. Victor Henderson, professor of neurology at Stanford Medical School, thus jokingly said that, to prevent Alzheimer’s, “don’t get old and choose your parents wisely.”

Alzheimer’s Risk Factors

Dr. Henderson subsequently pointed out, however, that the Alzheimer’s Association does publish “10 Ways to Love Your Brain,” steps that help prevent Alzheimer’s through addressing risk factors. Aerobic exercise, for instance, is linked to enhanced cognitive performance: in a mouse model, you see fewer beta-amyloid plaques, more blood vessel growth, enhanced memory, and new nerve cells in the hippocampus. Similarly, having continuous sleep is important for avoiding Alzheimer’s. In people who slept less than 6 hours a night, there was a great deal more beta-amyloid plaque with the hypothesis being that sleep is important to remove the abnormal buildup of beta-amyloid in the brain. Protecting the heart is also important because maintaining control over one’s blood pressure can help prevent strokes, which are associated with an 80% additional risk of developing dementia. Diet, of course, is also important as researchers have combined the DASH and the Mediterranean diets, characterized by eating greater vegetables, fish, nuts, whole grains as well as less red meat, sweets, and desserts; those who went on this combination diet were less likely to develop dementia. Finally, the Whitehall II study showed that social contact has neuroprotective effects because regular contact with friends and family has been linked to a lower risk of developing dementia.

Alzheimer’s Association 10 Ways to Love Your Brain

Much like with the cause, there is no definite means to diagnose Alzheimer’s. However, the diagnosis begins with the doctor taking a thorough history to understand the patient’s symptoms and what the family has seen happen with the patient. Having a history of other neurological issues may be a cause for concern as well as a family history of dementia because Alzheimer’s does run in families. Lab tests and a physical examination can help rule out other causes of Alzheimer’s symptoms while a neurological exam and brain imaging can help rule out other neurological diseases. Mental status tests such as a mini-mental state exam (MMSE), a 30-item questionnaire testing memory, attention, orientation, and other cognitive skills, and a mini-cog test, which gives patients a 3-item memory test and has them draw an analog clock at a certain time, can help doctors determine if a patient has dementia. Final confirmation, however, can only happen by examining the brain tissue at autopsy. No cookie-cutter means of diagnosing Alzheimer’s exists even today.

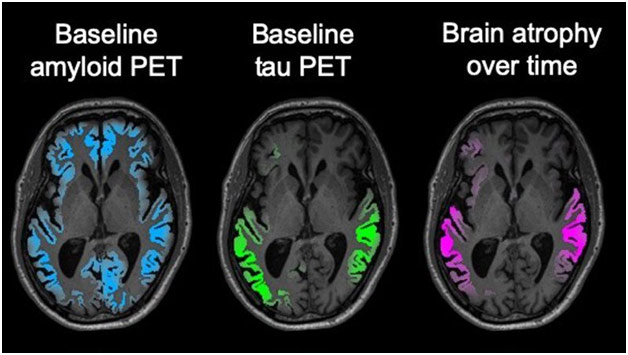

Unfortunately, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, and treatment is relatively limited, only mitigating symptoms for the most part. The drugs on the market are overwhelmingly targeted at slowing down the breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, a brain chemical important for memory because Alzheimer’s causes an acetylcholine deficit. Additionally, because the amyloid-hypothesis has dominated Alzheimer’s, most up-and-coming treatments are aimed at removing existing amyloid or decreasing the production of new amyloid with amyloid-destroying enzymes. However, Alzheimer’s drugs are notorious for not being translateable, working in animal models but not necessarily in humans. Tackling Alzheimer’s through beta-amyloid plaques may also not be the best strategy as UCSF researchers found that the location of beta-amyloid plaques had little bearing on which parts of the brain are more likely to atrophy. In fact, the location of tau protein, which has been mostly dismissed in the past, has better predictive power of where brain damage will occur. While beta-amyloid plaques certainly play a role, greater emphasis is now being put on tau proteins as a causative factor in brain atrophy instead of it being a result of brain atrophy, serving more as a “tombstone.” Drugs that target tau protein may end up enjoying greater success, but more work still needs to be done in that arena.

Baseline Amyloid PET and Baseline Tau PET Related to Brain Atrophy

Alzheimer’s is such a unique illness because so much is unknown from the cause to the diagnosis to the treatment. For patients facing Alzheimer’s, the disease can thus feel daunting and insurmountable. Awareness about what we do know about Alzheimer’s as well as new research is thus fundamental to helping patients manage their disease.

REFERENCES

https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet

https://www.alz.org/national/documents/topicsheet_betaamyloid.pdf

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/324425#How-tau-fibrils-elongate

https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

https://www.caringseniorservice.com/blog/alzheimers-statistics

https://www-scientificamerican-com.stanford.idm.oclc.org/article/how-exercise-might-clean-the-alzheimers-brain1/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4581900/

https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/frequent-social-contact-midlife-may-reduce-dementia-risk-whitehall-ii-study-analysis-shows

https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/how-dementia-progresses/symptoms-brain

https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2019/12/416296/alzheimer-tau-protein-far-surpasses-amyloid-predicting-toll-brain-tissue