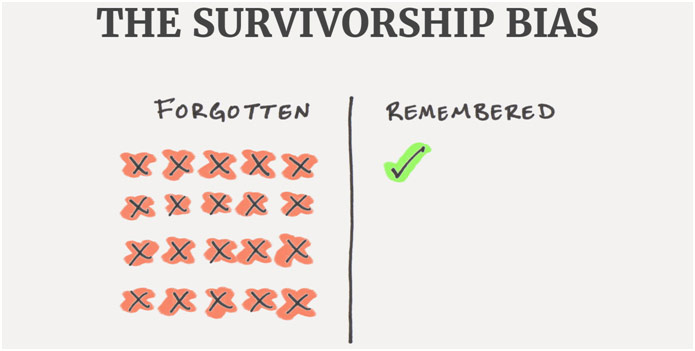

Survivorship bias is defined as “a cognitive bias that occurs when someone tries to make a decision based on past successes while ignoring past failures.” We, as humans, tend to look more at the success stories since they are so much more prominent and easy to access than the failures. Thus, we reach towards the light inspired by others, who have already reached the light and their methods, disregarding those who never made it (sometimes through using the exact same methods). This can cause mostly ineffective strategies to be thought to work extremely well because of some isolated successful cases, which can obviously cause problems, especially in the medical field.

Diagram of Survivorship Bias

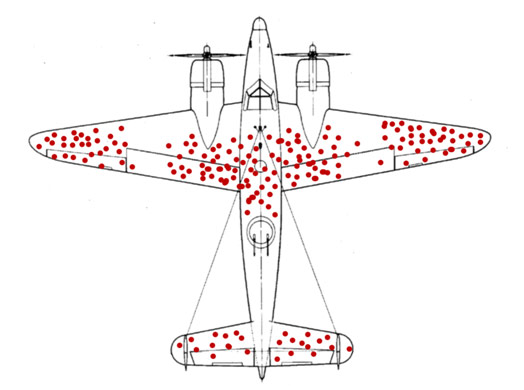

A great real-life non-medical example of the survivorship bias was explained by David McRaney, regarding WW2 bombers. In World War II, bombers often had a high risk of being shot out of the sky, leading to the destruction of the plane and the crew. The American Air Force was desperate for any way to give their pilots more of a chance of returning home safely, so they turned to statistician Abraham Wald. Engineers knew they could put extra armor on the plane, but they could only put so much before the planes would not be able to lift off. When looking at the bombers that made it back home successfully, the bullet holes were mostly around the center of the plane, the wings, and the tail gunner. The Air Force thought to put the armor there, but Wald showed that that strategy would not work. He reasoned that the places where there were bullet holes were places “where a bomber could be shot and still survive the flight home” (McRaney). The places where there was no damage were the places that needed additional protections because if there had been damage there, then the plane would have been shot down. The Air Force leadership had looked solely at the survivors and had not considered the planes that never made it back. By considering survivorship bias, Wald was able to save countless lives that would have been lost otherwise. Another simpler and more obvious example of the survivorship bias could be a long-time smoker at the age of 70 telling you that all those ads saying that smoking is harmful to health are false because he is healthy. While he truly may be perfectly healthy despite smoking a great deal, that one “survivor” does not disprove that almost half a million people die because of smoking and its associated diseases. As James Clear puts it, he may be surviving “in spite of his [habits] and not because of [them].” If we just looked at this person’s case and forgot all those who died, we would have a completely wrong perception of smoking.

Gunshots on the WW2 Bombers

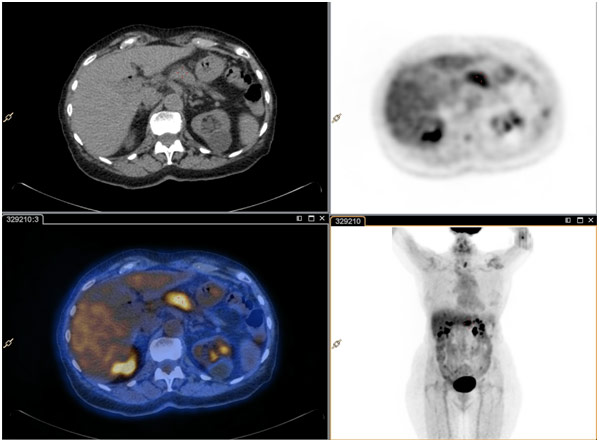

Survivorship also presents a problem in the medical aspect during clinical studies. My first example is about case-control studies of pancreatic cancer, which is when people with pancreatic cancer are compared to similar people without it in order to determine risk factors. Survivorship bias played a huge role in these kinds of studies because pancreatic cancer is so fatal, meaning that many patients with cancer could not physically participate in the study or have their risk factors assessed before they died. Therefore, researchers had to leave these huge portions of people out of the study. This presents a huge problem because certain risk factors that led to lower survival rates were not able to be documented as well, leading to an underestimation of that risk factor’s effect. Researchers looked at the survivors of the disease, who may not have had that deadly risk factor, ignoring those who had died because of that risk factor. Specifically, it was found that the effect of a large BMI and waist circumference was underreported due to survivorship bias. Thus, researchers, especially medical ones, must remain vigilant and address survivorship bias in their studies. Another major example is observational studies of the option of surgery to treat infective endocarditis (infection of the lining of the heart that often affects the valves). It compared mortality rates between patients who received surgical treatment to those who received medical treatment (no surgery). The study found that patients who received surgical treatment had overwhelmingly better outcomes than those who received medical treatment in terms of mortality; however, this study did not account for survivorship bias. It is common that surgery is not frequently done in the early stages when the patient is hospitalized for infective endocarditis, so patients who survive longer are more likely to get surgical intervention. Thus, all the people who died during the early hospitalization period (who did not even have surgery considered at that moment) were put into the medical treatment group. Only the survivors, in this case, were able to get the surgical treatment option, and the people who died were ignored by the surgical treatment group, being lumped into the medical treatment group, raising that group’s mortality rate. When corrected for survivorship bias, surgical treatment still had better outcomes than medical treatment, but only by a slight bit, representing how survivorship bias can cause serious deviations in results. Another consideration of survivorship bias is that doctors should strive to remember the patients where the treatment did not work as planned, resulting in the patient’s death. If they only remember the cases where the patient fully recovered (even though it may be the majority of the time), they may remain oblivious to something crucial, leading to unnecessary patient deaths despite the fact that it may be able to be remedied. Lastly, this bias can affect doctors who persistently do something wrong but feel empowered when it works for them. For example, a doctor may only order x-rays to try to diagnose appendicitis, which is usually not enough to do so, but the doctor finally gets a case where an appendix calcification is detected on x-ray, meaning appendicitis can accurately be diagnosed solely based on that. The doctor may feel like all the other x-rays were justified because of that one successful case even though an ultrasound or CT is proven to better than an x-ray alone at diagnosing appendicitis. To account for survivorship bias, the doctor needs to remember and learn from the times when the x-ray was not enough.

Pancreatic Cancer on PET/CT Scan

In general, survivorship bias plays a huge role in medicine whether it be in studies or in an actual clinic. It is always important to mentally note the presence of survivorship bias so that one can account for it at the end of the day. Often, survivorship bias can be extremely hard to discover, reinforcing the need for doctors and researchers to be on the lookout for them. Doing so can lead to a better understanding of diseases and better outcomes for patients, which is something that can always improve.

REFERENCES

Clear, James. The Survivorship Bias. James Clear, jamesclear.com/common-mental-errors. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

The Damaged Portions of Returning Planes Show Locations Where They Can Take a Hit and Still Return Home Safely; Those Hit in Other Places Do Not Survive. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Survivorship_bias. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Hu, Zhen-Huan, et al. “Role of Survivor Bias in Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Studies.” NCBI, 14 Nov. 2015, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5074341/. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

McRaney, David. “Survivorship Bias.” You Are Not So Smart: A Celebration of Self Delusion, 23 May 2013, youarenotsosmart.com/2013/05/23/survivorship-bias/. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.

Sy, Raymond, et al. “Survivor Treatment Selection Bias and Outcomes Research: A Case Study of Surgery in Infective Endocarditis.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/content/circcvoq/2/5/469.full.pdf. Accessed 23 Aug. 2017.