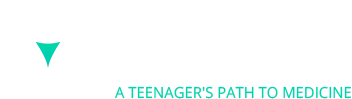

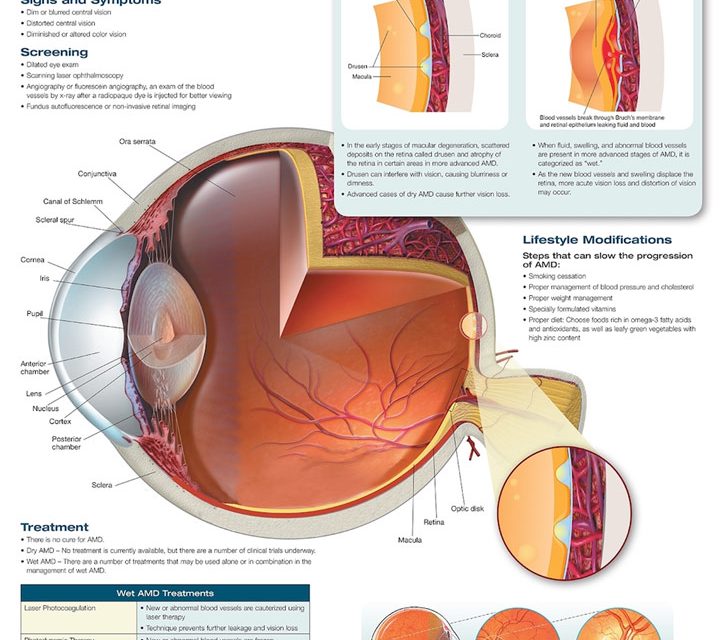

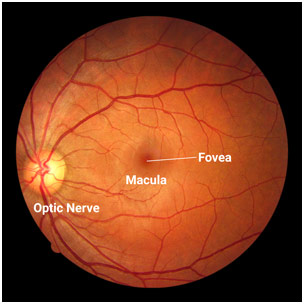

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading reason for vision loss in adults over the age of 50 with up to 11 million Americans having the disease, and this number is expected to double in 30 years. Importantly, macular degeneration is incredibly expensive, costing the WHO subregion that includes the United States, Canada, and Cuba $98 billion. To better understand macular degeneration first benefits from better understanding the anatomy and physiology of the eye. The first part of the eye is the cornea, the clear covering of the iris and pupil that protects the eye, bending the light as it passes through. Like a muscle, the iris, the colored part of the eye, then controls how much light enters through the pupil and to the inner eye. The lens immediately precedes the pupil and is a clear and flexible structure that focuses the light onto the retina, changing shape to allow you to see things at different distances. The retina is a layer of photoreceptors that detect images focused onto it before transmitting the information to the optic nerve to be taken to the brain for processing. The macula is an important region in the central part of the retina and is critical for our ability to see clearly. Thus, when the macula wears down in the case of AMD, there are vast implications for our sense of sight.

Macula on a Retinal Image

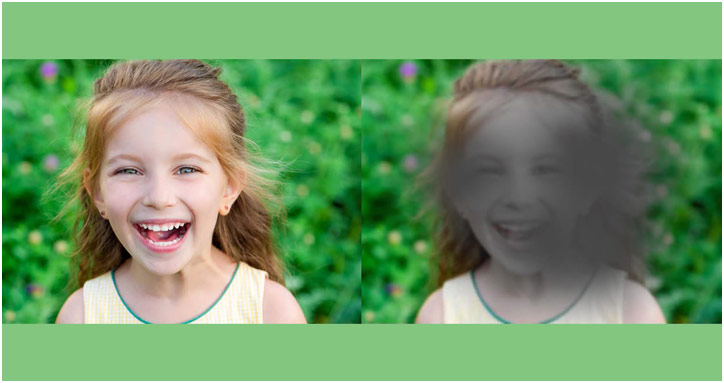

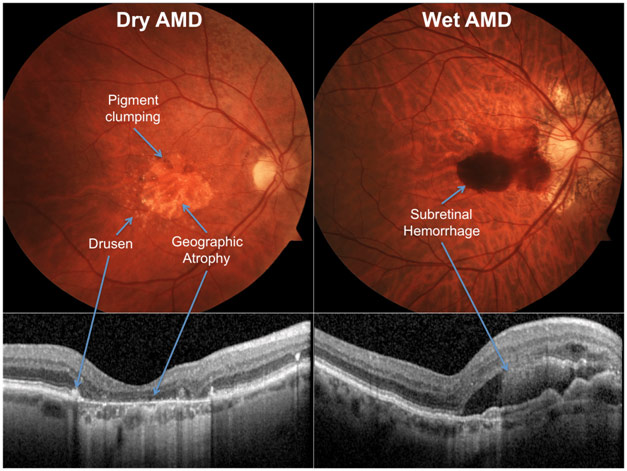

More specifically, the macula focuses on central vision, allowing us to read, drive, recognize faces, and most other important visual activities, so its deterioration can cause a person’s vision to be blurry. Specifically, the central region of a person’s vision can become shadowy and fuzzy, making it difficult to appreciate fine details in low lighting, while straight lines can be distorted or curved. Advanced AMD can even cause someone to be considered legally blind although they can still retain peripheral vision. Importantly, there are two types of AMD: wet and dry. Dry AMD is the most common type, affecting 80-90% of these patients although it is much less serious than wet AMD, which affects 10-20% of these patients. Dry (atrophic) AMD is characterized by the accumulation of drusen protein deposits in the macula, which causes vision loss over time as the proteins get bigger and more numerous, causing photoreceptive cells in the macula to die. Wet (neovascular) AMD, on the other hand, is when abnormal blood vessels grow and leak into the retina, causing swelling and fluid to accumulate onto the macula, which leads to sudden vision loss. Wet AMD is always preceded by dry AMD although dry AMD can advance to causing vision loss without converting to wet AMD.

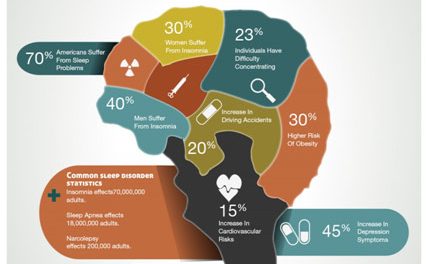

But what exactly causes AMD in the first place? Well, the number one risk factor is age as over 30% of adults over 75 have AMD. Race and gender are other risk factors with Caucasians and females being more likely to develop the disease. Smoking also increases the risk for developing AMD because of oxidative damage which can damage the retina’s ability to obtain oxygen, as does obesity and hypertension because both can damage the retina. Family history, as well, is understandably a significant risk factor for AMD. Unfortunately, however, nobody exactly knows the exact cause of AMD, which has stifled efforts to treat and cure the disease.

Normal Vision and AMD Vision

A series of tests can help to diagnose AMD: fundus photography, the Amsler grid, fluorescein angiography, and optical coherence tomography (OCT). The fundus photography is the traditional retinal scan that can provide detailed color pictures of the retina, showing drusen, blood, scar tissue, atrophy, and more. The Amsler grid, on the other hand, is a grid of perpendicular lines, much like graph paper, with a dot in the center that helps to detect defects in a central vision: patients with AMD will see the lines in the center to be unclear, distorted, or wavy. This visual field test, however, can be supplemented by fluorescein angiography where the yellow fluorescein dye is injected into the patient’s vein with a camera then helping to visualize the blood vessels in the eye, an important diagnostic test to detect wet AMD. OCT is another imaging technique, which noninvasively takes high-quality pictures of the retina and macula to determine changes in thickness. All of these can help to diagnose AMD and allow for more rapid treatment.

Treatment can stop the progression of AMD; however, it cannot rescue lost eyesight, reinforcing the need to have treatment be immediate. For dry AMD, the National Eye Institute found that supplements, namely vitamin C, vitamin E, lutein, zinc, copper, zeaxanthin, and beta carotene is taken together, can reduce the risk of vision loss for dry AMD patients. With an intraocular injection, anti-VEGF drugs, such as ranibizumab and aflibercept, work to stop new blood vessels from leaking in the retina by blocking angiogenesis, new blood vessel formation, for wet AMD patients. Similarly, photodynamic therapy uses a laser in conjunction with a light-sensitive drug in order to destroy extraneous vessels in the eye, again for wet AMD. However, there, unfortunately, is no cure of AMD, reinforcing the need for greater research and work in this area.

Fundus Photography (above) and Optical Coherence Tomography (below) for Dry and Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration

As the leading cause of blindness among the elderly, age-related macular degeneration is a devastating ocular disorder for which scientists do not know the cause or a cure. There is incredibly encouraging research pushing the envelope of what is possible with retinal cell transplants, stem cell therapies, and computer chips stimulating vision. The future looks bright for patients with AMD and their families.

References

Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Anatomy Stuff, www.anatomystuff.co.uk/media/catalog/product/a/g/age-related-macular-degeneration-poster.jpg. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.

“Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Diagnosis and Tests.” Cleveland Clinic, 21 Dec. 2020, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15246-age-related-macular-degeneration/diagnosis-and-tests. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.

“Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Facts & Figures.” BrightFocus Foundation, 5 Jan. 2019, www.brightfocus.org/macular/article/age-related-macular-facts-figures. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.

The Back of an Eye Photographed with an Ophthalmoscope. 29 Aug. 2013. Fighting Blindness Foundation, www.fightingblindness.org/research/the-pseudofovea-how-the-retina-adapts-to-central-vision-loss-2754. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.

Brazier, Yvette. “What Is Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)?” Edited by Ann Marie Griff. Medical News Today, 7 June 2018, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/152105#treatment. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.

Dry and Wet AMD. 21 July 2020. Thailand Medical News, www.thailandmedical.news/news/amd-or-age-related-macular-degeneration-researchers-identify-vitronectin-as-new-drug-target-for-dry-age-related-macular-degeneration. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.

Kattouf, Valerie. “What Is Macular Degeneration?” All about Vision, www.allaboutvision.com/conditions/amd.htm. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.

“Macular Degeneration: Prevention & Risk Factors.” BrightFocus Foundation, 5 Jan. 2019, www.brightfocus.org/macular/prevention-and-risk-factors. Accessed 23 Dec. 2020.