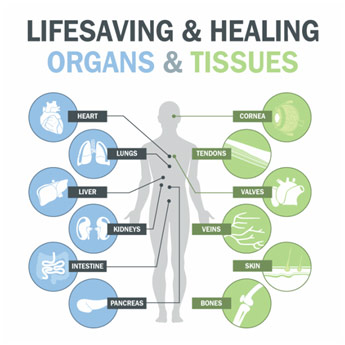

Several months back, I took a Dartmouth CME Course on organ and tissue donation that gave me insight into the entire process. This is extremely relevant now in April as it is National Donate Life Month, which is celebrated to “help encourage Americans to register as organ, eye and tissue donors and to celebrate those that have saved lives through the gift of donation,” according to Donate Life. The problem they are tackling is severe as 20 people die in the US every day, desperately waiting for a lifesaving organ. The demand for these organs far exceeds the supply, and most people on the national transplant list never receive their organs. Awareness about the issue is extremely important since one organ donor can save up to 8 lives with their heart, liver, pancreas, intestine, two lungs, and two kidneys. In addition, an organ and tissue donor can improve the lives of several more people by donating their corneas, skin, heart valves, bones, and more. Thus, it is important to be knowledgeable about the organ and tissue donation process that transforms so many lives.

Organs and Tissues That Can Be Donated

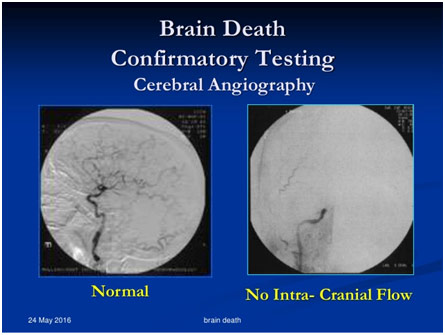

The process of donating organs often begins with circulatory or neurologic death. Neurologic death is generally after a severe brain injury or some other severe neurological event like a spinal cord injury. The brain may stop functioning, which may require the patient to be put on a ventilator to maintain their breathing, which helps keep the heart beating. A ventilator is not a long-term solution, however, and the heart will slowly deteriorate in such conditions. Often it becomes clear that the patient is brain dead, but there are certain criteria to make this definite diagnosis of brain death. The patient needs to be in an unresponsive coma, have an absence of brainstem reflexes, and have an absence of respiratory function with an apnea test. If there is any uncertainty after doing these primary tests, transcranial doppler, electroencephalogram (EEG), and cerebral angiography all are good options for secondary tests. Patients may also be subject to circulatory death, which is declared after the internal circulation ceases. The patient loses the function of their heart and lungs. Donation after cardiac death (DCD) becomes a little more complicated since there are few ethical issues regarding it since organs must be harvested quickly after death to prevent deterioration. There is often a misconception that doctors will let a patient die in order to harvest their organs and tissues if they choose to become an organ and tissue donor. That they will be hovering over the patient, not treating them. However, this could not be further from the truth since a doctor takes an oath to first work tirelessly to save their patient’s life. Even if they did have this ulterior motive, it would mean that the doctor would work even harder to treat the patient since critical organ function may be compromised if they stop.

Cerebral Angiography in Normal Patient and Brain Dead Patient

When actually given consent to harvest the organs though, the doctors have to move fast to be able to save the organs since function quickly deteriorates. Often, the doctors may even begin conversations about organ and tissue donation with the family before death when it is clear that there is very little a doctor can do to help the situation. For example, the doctors may approach the family when the patient progresses to brain death or when the family chooses to withdraw medical treatment. In either case, the family’s consent will be needed to harvest the patient’s organs. When asked at the right time by the right person, 75% of families will consent to an organ and tissue donation. For the families that do not consent, understanding why is paramount since with proper explanations from the doctor, these families may genuinely realize that they want to consent. The biggest cause of a family’s refusal, interestingly enough, is a family’s denial and rejection that their loved one is brain-dead. When on a ventilator, the patient will feel like they are alive to any outsiders since their skin will be warm to the touch. Thus, families will refuse to accept their death as long as the heart keeps beating, which represents a problem because the organs will slowly deteriorate. This means that clinicians must work together to find ways to unequivocally confirm brain death, and they must be able to effectively communicate this fact to the patient’s family so that they can sufficiently understand the situation. Another big reason that often pops up is that people believe that their religion is against organ and tissue donation. This happens to be untrue since all major religions, including Christianity; Islam; Judaism; Hinduism; Sikhism; and many more, support organ and tissue donation, saying that it is an honorable and righteous act. Thus, this should not represent a barrier to the patient’s family since religious beliefs actually encourage such noble acts. The last major reason for a patient’s family refusal is that these families may not know what their family member (the patient) would have wanted to do. Thus, they take the safe option and refuse since they do not want to go against the member’s last wishes. The way to resolve this problem is simple since it only entails having an honest conversation about what should a family do, in regards to organ and tissue donation, if one family member was to, unfortunately, lose function of their vital organs, diminishing their chance of survival. These conversations clear up any confusion and allow for certain decisions by the family. With proper steps by the patient and doctor alike, more families may become willing to donate their organs and tissues, which translates to more lives being saved or improved.

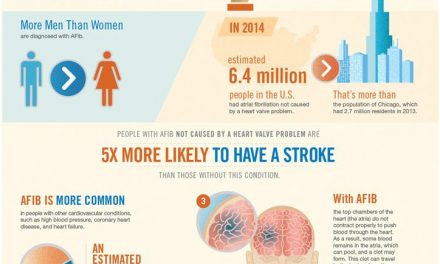

National Donate Life Month Poster

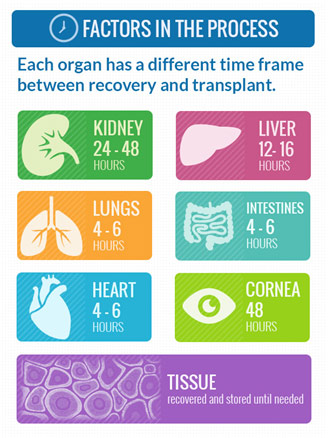

The organ procurement and transplantation network (OPTN) is a program started by the federal government that helps recover and place organs where they need to be, working with hospitals around the nation. They work hard to select recipients based on how compatible the organ is, how urgent the organ is needed, the distance the recipient is away from the donor, and other medical criteria. They do not discriminate based on gender, race, income, and other such factors to ensure that nobody is getting special treatment. Once the OPTN locates the proper recipient, surgery is done at the quickest possible instance to recover the organ from the donor and to transport it to the recipient. The timing of the organ removal is carefully coordinated in order to preserve the organ and to avoid the narrow window of viability. For instance, a heart can only be outside for 4-6 hours before it loses it viability. When carefully done, recovery and transplant can occur very smoothly and be highly successful.

Organ’s Viability Time Frame

Organ and tissue donations make an enormous difference to the people who receive them. Often this gift can help a family get through a loss rather than getting over it since their loved one was able to make an enormous life-changing difference to some people somewhere. Perhaps if we all understood the difference we could make and agreed to become organ donors if a tragic event were to take place, the nearly 120,000 people who need a life saving organ transplant would be able to lead normal healthy lives.

References

Brain Death Confirmatory Testing. Slide Share, www.slideshare.net/SolomonAlemu2/brain-death-presentation. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

Chassé, Michaël, et al. “Ancillary Testing for Diagnosis of Brain Death: A Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” NCBI, 9 Nov. 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3828391/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

Donate Life Month. Small Beats, smallbeats.childrensomaha.org/donate-life-month-tackling-4-reasons-why-people-dont-become-organ-donors/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

Each of These Can Save or Heal a Life. Life Share, www.lifeshareoklahoma.org/about-donation.html. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

Factors in the Process. Donors Matter, www.donorsmatter.pitt.edu/unit-4/time-frame-organ-process. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

Organ Donation Process. Donor Alliance, www.donoralliance.org/understanding-donation/about-donation/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

“Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.” HRSA, 23 Nov. 2017, optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

Stein, Rob. “Changes in Controversial Organ Donation Method Stir Fears.” The Washington Post, 19 Nov. 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/changes-in-controversial-organ-donation-method-stir-fears/2011/09/15/gIQAlY9agK_story.html?utm_term=.a14f4dbd7e98. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.

“What Can Be Donated.” Organ Donor, organdonor.gov/about/what.html. Accessed 25 Nov. 2017.