Beneficence and non-maleficence are two of the most fundamental pillars of medical ethics, reflecting doing good and not doing harm respectively. However, there is an uncomfortable tension between these two pillars because medicine sometimes necessitates doing harm for the hope of doing good. Take chemotherapy, which devastates our cells to help shrink the size of a tumor, or surgery, which deliberately causes trauma to perhaps save the patient’s life. Clearly, there is an important distinction between the pillars of beneficence and non-maleficence despite them seeming essentially the same. Doing good suggests the physician must actively do something while not doing harm suggests the physician must refrain from doing something. Omission bias reflects the psychological tendency towards inaction over action because we judge harmful action harsher than harmful inaction.

understanding-cognitive-biases-omission-bias

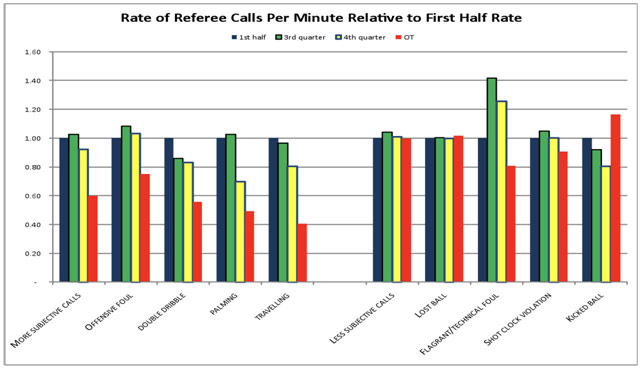

It proves helpful to first consider some nonmedical examples of omission bias. In sports games, referees are often more wary of making an incorrect call (action) than failing to make a correct call (action). Indeed, the number of calls referees make has been shown to decrease in closing parts of sports games or when the score becomes neck-to-neck. In both cases, referees are unwilling to make a mistake with passions running high on both sides, so they avoid making a call as much as possible. Another example is related to the bystander effect. Imagine Person A pushed a kid into a pool and that kid almost drowned. Then imagine Person B saw a kid drowning but did nothing so that kid also almost drowned. In both cases, the effect is the same, yet we tend to view Person A’s action more harshly than Person B’s inaction despite both being rather despicable. Omission bias can have devastating impacts on medicine because, for one reason or another, rational action gives way to meaningless inaction.

Rate of Referee Calls by Quarter Timing for the NBA

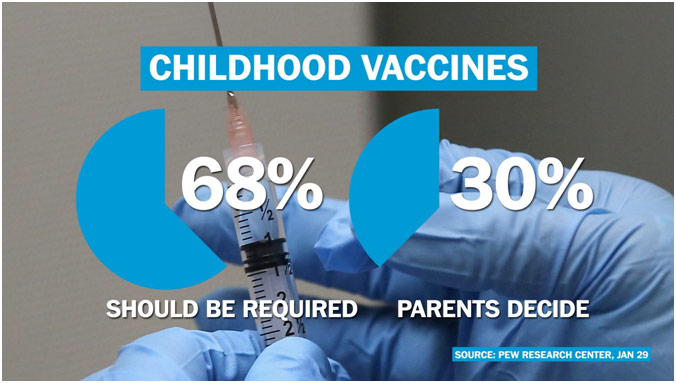

In medicine, the debate over vaccinations is one of the most common examples of omission bias at work. Take an example where a viral epidemic kills 10 people for every 10,000 but the vaccine for this virus kills 5 people for every 10,000. The choice seems fairly obvious in that the vaccine should be given to everyone because it prevents double as many deaths. However, some parents do not even want to take that reduced risk because they would feel more culpable if their child had an adverse reaction to the vaccine (“If only I had not given my child the vaccine…”). Given the same exact devastating outcome, some people would prefer to take no action because doing nothing offloads the blame from their shoulders and onto the abstract forces of nature and destiny. Action can be much harder to emotionally deal with than inaction.

Omission bias also plays a role in the physician-assisted suicide debate. Consider two terminally ill patients. With consent, a physician gives Patient A a lethal medication to end Patient A’s suffering. In the other scenario, a physician discontinues Patient B’s therapy, and Patient B passes. In both cases, the effect is the same, but physician-assisted suicide is significantly more controversial than the discontinuing of treatment: action is penalized while inaction is innocuous. Omission bias is most detrimental, though, because it causes us to lose sight of the fact that the decision about life is ultimately the patient’s own.

The statistic about Childhood Vaccines Being Required or Not

Discouragingly, omission bias also infiltrates other aspects of clinical decision making. To simply put it, a patient’s deterioration is more anodyne if it can be ascribed to the disease’s natural progression. If a physician’s intervention causes or is even coincidentally succeeded by the patient’s deterioration, suddenly everybody is up in arms. Omission bias contributes to why surgeons are often unwilling to take on difficult cases: future complications may come back to haunt them. Thus, the physician’s incentives are inverted. It may be safer to not treat some patients even if the treatment is genuinely beneficial and recommended by the literature for that patient.

Physicians may also take unnecessary efforts to confirm their diagnosis, delaying evidence-based treatments and contributing to increasing health care costs to cover their tracks, at least legally speaking. A study published in Chest surveyed 125 pulmonologists and found that they were significantly more likely to follow published guidelines when it meant taking no action (i.e. not ordering a CT scan) than when it meant taking action (i.e. canceling an unnecessary CT scan). These physicians were not willing to cancel the superfluous CT scan perhaps because doing so put them at risk in case the CT scan returned something notable, no matter how unlikely this may be. We have become a nation where physicians regularly practice defensive medicine, and some of the blame can be traced to omission bias. If forced to act, physicians want to be unrealistically sure that they are correct about everything.

Cartoon Regarding Defensive Medicine

While modern medicine often succeeds at saving lives, it sometimes falls short. Physician-related errors account for a dispiriting proportion of lives lost in a hospital, and psychological biases certainly play a role in this tragedy. We must place greater emphasis on addressing biases like omission bias, perpetually reminding ourselves that action and inaction must be treated equally if the effect is similar. It should never be detrimental for physicians to use guidelines and evidence-based medicine to treat their patients. Ultimately, medicine is about giving the best quality care to patients. No external concerns should stop physicians from doing that.

Childhood Vaccines.

29 Jan. 2015. The Washington Post, www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2015/02/04/the-political-vaccine-debate-explained-video/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.

Cognitive Bias. Label Rebel, labelrebelofficial.com/44-understanding-cognitive-biases-omission-bias/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.

Defensive Medicine. Medium, medium.com/healthy-communities-weekly/defensive-medicine-272526f760d. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.

Dobler, Claudia, et al. “Clinicians’ Cognitive Biases: A Potential Barrier to Implementation of Evidence-based Clinical Practice.” BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, vol. 24, no. 4, 2019, pp. 137-40, ebm.bmj.com/content/24/4/137. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.

Levy, Neil. “Vaccination and Omissions Bias.” Practical Ethics, 13 Feb. 2015, blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2015/02/vaccination-and-the-omissions-bias/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.

Pricing Transparency. Dignity Health, www.strosenh.org/pricing-transparency/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.

Rate of Referee Calls per Minute Relative to First Half Rate. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, siepr.stanford.edu/system/files/Stanford-%20wertheim.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.

Wertheim, L. “The Omission Bias in Sports.” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, siepr.stanford.edu/system/files/Stanford-%20wertheim.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct. 2019.