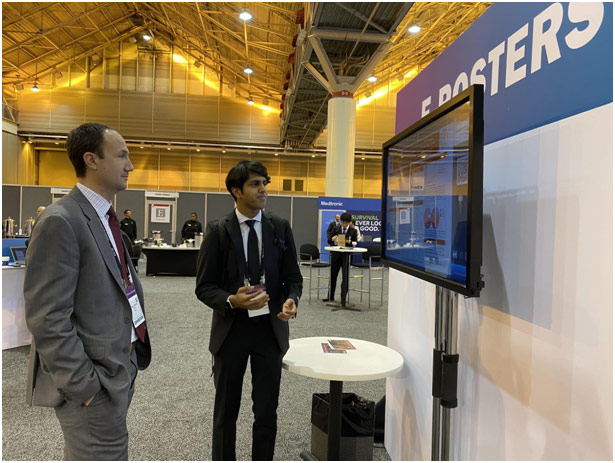

I had the great pleasure of going to the 56th annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in New Orleans, Louisiana to present my research “Cardiothoracic Surgeons Who Stay on as Faculty at Their Training Institution Demonstrate Greater Academic Productivity Over Their Careers” as an ePoster. With a team at the Stanford Cardiothoracic Surgery Department, we made a database of all academic cardiothoracic surgeons in the US and found that institutional continuity from one’s training to the first job is correlated with a greater number of publications, those publications having a higher impact, and a greater likelihood of achieving NIH funding. One of the implications of our study was that institutions should further enhance mentorship networks and academic start-up resources to support these first-time faculty arriving from different institutions. In this second part of a two-part series, however, I want to discuss some of the sessions I attended at STS 2020.

Presenting my e Poster at STS 2020

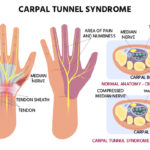

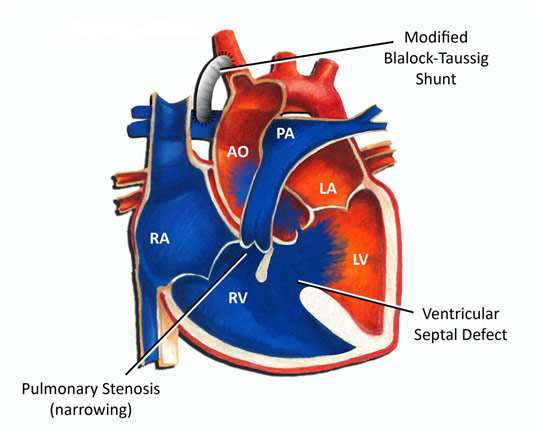

The Vivien T. Thomas Symposium saw Dr. Clyde Yancy, a past president of the American Heart Association, discuss the importance of diversity through the example of Vivien Thomas, an African American man who never went to medical school but trained dozens of residents and helped bring in the dawn of a new era in cardiothoracic (CT) surgery. Specifically, Dr. Thomas—Johns Hopkins gave him an honorary Doctor of Law because they could not give him an honorary medical doctorate—worked with Dr. Alfred Blalock to revolutionize treatment for blue baby syndrome through the Blalock-Taussig shunt. The blue baby syndrome occurs when a baby’s blood cannot carry oxygen around the body, so the baby becomes cyanotic and the color blue. A Blalock-Taussig shunt is a small tube that takes blood from the aorta to the pulmonary artery so that the blood can go to the lungs and pick up additional oxygen. While only a temporary palliative fix, the Blalock-Taussig shunt has had an unparalleled impact on saving the lives of those affected with blue baby syndrome.

Dr. Thomas was a grandson of a slave, and, unable to go to college as he dreamed to, he became a carpenter. Following the Great Depression of 1929, however, he became a surgical research assistant in the Blalock lab at Vanderbilt where he was officially hired as a “janitor” due to his race. His contributions to better elucidate the mechanisms of shock, a condition where the body is not getting enough blood, and develop a treatment for shock were some of his most impactful work. Soon after, Dr. Blalock was offered a job at Johns Hopkins, but Hopkins was not willing to take Dr. Thomas, again because of his race. Through Dr. Blalock’s steadfast support of Dr. Thomas, declaring that they were a package deal, however, both of them moved together. Nonetheless, at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Thomas was paid as a janitor even though he worked as a lab assistant, lived in the segregated Oliver, Maryland instead of Baltimore, never felt comfortable wearing a white lab coat, was never a co-author on any publication, and did part-time work as a bartender to support his family. In fact, only after 37 years at Hopkins did Dr. Thomas receive a faculty appointment as an Instructor of Surgery.

Dr. Vivien Thomas’ story is not one about discrimination and inclusion but one about allyship and sponsorship. Dr. Thomas asked Dr. Blalock for a job, and Dr. Blalock invested in him as a person. Dr. Yancy used Dr. Thomas’s story to discuss how diversity is a path towards excellence, a means towards accomplishing quality health outcomes and creating better science. The impact of a lack of diversity is clear in cardiovascular care: for aortic stenosis, a narrowing of the aortic valve, African Americans and Hispanics are 32% less likely to get a TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) despite outcomes being no different than for Caucasians. The root of the problem is biased, defined by Dr. Yancy as a persistent and pernicious preference for a social group that is unconscious and automatic. The thing, Dr. Yancy explained, is that all people are affected by bias: it is a function of the world we live in. Awareness about our ever-present implicit bias, however, allows us to intervene in a positive way. Dr. Yancy ended his talk by emphasizing how bias can be overcome with awareness, allyship, and sponsorship.

Blalock-Taussig shunt for the Tetralogy of Fallot Congenital Defect

At STS, I also encountered a series of fascinating talks on heart transplantation from CT surgeons from all over the country that I want to dive into here.

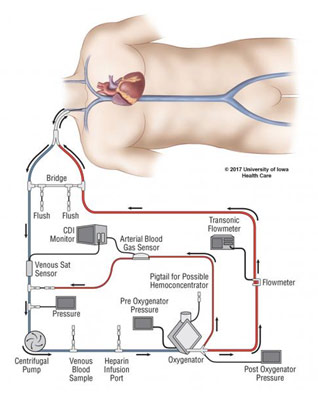

Dr. Ahmet Kilic from Johns Hopkins spoke about ECMO, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, which is used as a bridge to heart transplantation. However, ECMO is greatly scrutinized because it has only a 60% survival rate. Dr. Kilic reminded us, though, that this number also suggests that 60% of patients would have died if they were not offered this therapy. Here, the French experience with ECMO gives important lessons as France previously also had poor outcomes with ECMO because the population receiving ECMO were sicker patients who had acute renal insufficiency and/or mechanical ventilation. The truth is that VA (veno-arterial) ECMO can be used safely with one-year survival rates of 86% at centers when ECMO implantation was a relatively high percentage of case volumes. To utilize ECMO safely, Dr. Kilic emphasized that you need readily available donors—ECMO is a bridge to transplant after all—and cannot have liver or lung dysfunction. Dr. Kilic ended his talk emphasizing the benefit of ECMO: it is a definitive therapy for patients who are going to die with its success correlated to a highly selective population, the reduction of periprocedural complications, a short time from ECMO to a heart transplant, and a continuation of ECMO after transplant for support.

Dr. Francis Pagani from the University of Michigan spoke about getting hearts for transplantation with donation after circulatory death (DCD). To put it simply, heart transplantation is an effective leading treatment for advanced heart failure, but its epidemiological benefit is limited by a number of available donors and restrives transplant criteria, which underlines the need to increase donor availability. The current standard is donation after brain death (DBD). In fact, in the US, the first DCD transplant was actually only in 2019 because of rules that organs cannot be acquired if the potential donor died of circulatory death. Given the shortage of hearts though, Dr. Pagani emphasized that DCD is clinically necessary. The experience in the UK and Australia have shown that DCD is also a viable alternative to DBD because ex vivo perfusion, pumping blood through a donor organ while it is being transported, can extend the usability of the heart for a number of hours. The use of DCD hearts for transplantation is so promising because it is estimated to increase available heart donors by 20-30%. Furthermore, using ex vivo perfusion of DCD donor hearts results in similar outcomes as DBD donor hearts. The Australian group even showed that the DBD group had greater mortality than the DCD group. DCD heart donation is thus a viable strategy to increase the number of donor’s hearts in the US as early experience in the UK and Australia has demonstrated the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of DCD heart organs.

ECMO Diagram

Dr. Ashish Shah from Vanderbilt spoke about how to increase the number of hearts available for transplantation. The goals of heart transplantation are to avoid mortality, disability, primary graft dysfunction, and coronary artery disease among other things. Interestingly, Dr. Shah highlighted how surgeons typically do not want to use female organs for heart transplantation because they tend to be smaller, but there is only a 4% difference in survival rate after five years when comparing female and male donor hearts. In fact, heart mass has better discriminatory power for determining size match than gender does. In another interesting point, Dr. Shah spoke about how CT surgeons typically do not want to take hearts from older patients, which means that only 30-40% of donors have hearts usable for transplantation. Cedars Sinai uses hearts from only 13% of donors above the age of 50, and that is on the extremely high side with Vanderbilt using only 1% of donor’s hearts from patients above the age of 50. For comparison, liver transplant surgeons usually take the liver regardless of age. Using more hearts from older patients might thus be a path forward. Additionally, taking hearts from DCD donors, as discussed by Dr. Pagani, and using Hepatitis C hearts after cleansing the organ might be other ways to increase the number of donor hearts available.

Dr. Mara Antonoff from MD Anderson spoke about using social media to increase donor hearts for transplantation. For surgeons, social media, of course, has a practical purpose because it can be used to promote surgeons’ practices, herald their clinical achievements, educate the public, and connect with other surgeons. For patients, it can foster networking between transplant recipients and donors, promote the benefits of transplant donation, and enable philanthropy for patients who need a transplant. Given that over 113,000 patients in the US are waiting for a transplant with 20 patients dying every day because of the lack of organs, there is a great need to increase the donor pool, which has stayed relatively stagnant over the years. The impact of social media on transplantation has been shown elsewhere with 7.4% of blood donors using social media as a reason for donating. The thing is that patients are also ready to leverage social media to their advantage with 51% of kidney transplant patients willing to post information about living kidney donation on social media. The University of Wisconsin and the state of Michigan actually focused on using social media to help increase organ donation registries with social media ads increasing registrations twice over the baseline. Dr. Antonoff emphasized that CT surgeons can and should educate patients about how to share their transplant stories, promote organizations that help educate people about organ donation, and encourage departments to share stories of success and links to information about how to become an organ donor.

Baylor Live-Tweeting a Heart Transplantation Surgery

Attending STS was a spectacular experience for me to learn more about medicine at the highest level through informative sessions filled with impactful presentations. It was such a privilege to be able to attend this national surgical conference as a high school student, and I truly enjoyed every moment of it.

REFERENCES

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321955.php

https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/article?contentid=1657&language=english